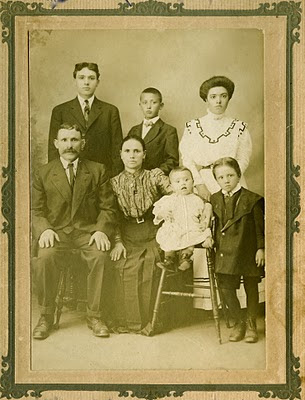

Ralph Schiavon

Halcyon Days

(Third of a four-part series about my maternal great-grandfather)

A self-made man, my grandfather, Ralph Schiavon, was not afraid of anyone. Not even “Scarface” Al Capone.

In the late 1920s, Ralph was working as a supervisor for the Internal Revenue Service and lived on the South Side of Chicago with his wife Alice and their two small children, Tom and Joan (my mother), when two of Capone’s henchmen summoned him to the mobster’s infamous headquarters in the Windy City at the Lexington Hotel. There, he was asked to help a paesan, “Mr. Capone,” to straighten out the books,” for which he would receive a handsome recompense. As Ralph sat there listening to the men, his mind was racing.

As an employee of the IRS, he surely was aware that Al Capone was under scrutiny for tax evasion. Though Capone ran a number of illegal gambling and bootlegging operations, he made sure all his assets and properties were not in his name but in those of his frontmen. He had never filed an income tax return or declared any taxable income or assets.

Ralph knew he was in a delicate situation. The request for an IRS agent’s help was brazen enough, but the thought that he should regard Capone as his paesan might have rankled him, too. While he knew there could be consequences for saying no to Al Capone or his henchmen, he was a moral man with a strong sense of integrity that was far greater than any fear he might have felt. Thanking the men for the offer, he tactfully said he could not be of much help and was astounded when he was dismissed summarily. He hurried home, looking over his shoulder all the way for fear of reprisals against him or his loved ones. Fortunately, nothing ever happened. He must have breathed an enormous sigh of relief in 1932 when Capone was convicted of tax evasion.

Like many Americans at the time, Ralph’s job fell victim to the Great Depression, and he and Alice found themselves in dire financial straits. To ease the burden, they sent my mother, then two years old, to live with Alice’s mother and maiden aunt until they were able to get back on their feet some four years later. It was as though history was repeating itself, as Emanuela Schiavone had sent her own toddler Ralph to live with two maiden ladies so many years before in San Sossio.

Ralph had always been resourceful and was able to find a job at a grocery store. Though it was a better place than most to work during such hard times when many people were starving, it just helped the family get by.

Still regretting that he could not attend college, Ralph determined not to let this happen to his youngest brother, Leo, who had shown great academic promise. He mustered enough money to send Leo to college, first to the University of Chicago and then to Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana. This was no small effort, considering he began the endeavor around 1928 and was somehow able to see it through to Leo’s graduation from Notre Dame in 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression. It must have taken a great deal of sacrifice, but Ralph loved his brother very much and believed Leo was worth the effort.

It was a proud day for the Schiavones. Indeed, it was a special day for all of Revere when Leo graduated from Notre Dame cum laude. He was the first Italian-American from the town to graduate from college, and the mayor threw a party at City Hall and invited everyone to celebrate the accomplishment. Leo went on to earn an advanced law degree at DePaul University in 1934 and was hired by a Chicago law firm, eventually repaying his brother in full.

Ralph established his own practice as a tax consultant with an office at the Title & Trust Building at 111 West Washington Street in downtown Chicago. As things improved, he and Alice took a vacation to Cuba. Upon their return in 1933, they brought their daughter (my mother), Joan, then five years old, back home to live with them again.

On May 4, 1935, Vito Schiavone, Ralph’s father, afflicted for several years with arteriosclerosis and kidney disease, suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. He died a week later at the family home at 33 Eastern Avenue in Revere. Ralph brought his mother, Emanuela, to live with him and his family for a short time afterward. She later returned to Revere and moved in with Ralph’s sister, Filomena Schiavone Scicchitani, and her husband, Tommasso, for most of the remainder of her life.

Filomena herself would die an untimely death a few years later, on October 23, 1941. On the evening of her death, she had received an award at an American Legion banquet for her involvement in local Democratic politics and was returning to her seat when she collapsed of a cerebral hemorrhage, as had her father.

Her death came as a terrible shock to her brothers, who loved her dearly. Years later, her daughter, Gloria (Scicchitani) Johnson, recalled the funeral procession from the church to the Scicchitani home at 48 Eastern Avenue stretched for blocks, with family, friends, and local politicians in attendance.

My mother worshipped her father and fondly remembered his tenderness to her as a child. In contrast to his own stern upbringing, Ralph never spanked her or Tom. Not long after Joan had been brought back home, she broke a favorite mirror of her mother’s. Alice was furious and sent Joan to her room to wait for a spanking from her father when he got home from work. My mother later described the incident in her autobiography:

“All afternoon, I worried. My father had such BIG HANDS! ‘This will be some spanking,’ I thought. The hours passed, the front door opened, and there was my Daddy…so BIG. He had a smile on his face, which quickly disappeared as my Mother told him of my misbehavior. A stern, serious expression crept across his face, and I stood there, grasping my Mother’s dress hem, trying to disappear behind her.

“My father grunted, ‘Come with me.’ I followed as slowly as possible, cringing inside with fear. We entered the bathroom; my Father closed the door, turned to me, and asked if I was sorry for what I had done. In a small voice, I replied that I was very sorry and promised never to do it again.

“In the meantime, my Mother, waiting outside in the hall, was having second thoughts about my punishment. A smile appeared on my Father’s face, and he plotted with me to clap his big hands together, and I would scream as loud as I could. . . My Mother called out for my Father to stop spanking me. We opened the door with big smiles, I in my Father’s arms. From that time on, there was a special bond between (us), as through my life, (he) tried to shield me from harm.”

|

My great-grandfather, Thomas McGinnis, built this home on

South Drexel Avenue for his family in 1913; after he

and my great-grandmother Mary Jane died, my grandparents

Ralph and Alice Schiavon moved their young family here.

|

When Alice’s mother, Mary Jane (Gaffney) McGinnis, died in the summer of 1940, the Schiavons moved into the McGinnis family home on South Drexel Avenue, on Chicago’s South Side, where they lived for several years before moving to a larger home on Saint Lawrence Avenue. Ralph loved these homes with their large gardens and spent long hours digging out weeds, planting flowers, and trimming hedges. He loved working with his hands. Maybe he felt connected to his roots, especially his Sannella grandparents, who had been gardeners by trade in San Sossio.

|

Ralph Schiavon in his garden on

Saint Lawrence Avenue, Chicago. |

Ralph traveled back to Italy at the end of World War II and was shocked by the poverty and devastation there. The large number of children who had been orphaned during the war especially moved him. He befriended a young priest, Father Piccinini, who ran an orphanage in Southern Italy, and he began sending funds to assist this and a number of other postwar relief efforts.

In 1946, the Schiavon’s eldest child, Ralph Thomas, known as “Tom,” married Angelina Ciliberto, a strikingly lovely brunette from Iacurso, Calabria, Italy. They went on have four children: Ralph, Alice, Michele, and Paul.

Alice had taken up several hobbies that included doll and stamp collecting. Over the years, she also became an avid collector of fine antiques. Ralph supported her in these interests and helped her open an antique and gift gallery, Chatham Galleries. In 1950, he sent Alice and Joan to Europe on the luxury liner Queen Mary on an antique-buying trip.

While Alice was delighted at the prospect of going off to Europe to hunt for new treasures, Joan, 21 at the time, balked at the idea. She envisioned herself trapped for months among a boring melange of older people and even older antiques. Ralph saw the trip as an opportunity for his sheltered daughter to be exposed to a rich world of culture, tradition, and history. He arranged for my mother and grandmother to stay in the finest staterooms and hotels and tour the most beautiful cities on the continent. It would be the trip of a lifetime for my mother, who returned to New York from Cherbourg, France, on the cruise liner Queen Elizabeth I as a wiser and more worldly young woman, thanks in large part to her father’s vision and encouragement.

Sometime during the 1950s, the governor of Illinois appointed Ralph as State Bail Bondsman Inspector. He continued his tax consulting business, commuting by train daily to his office in the Loop downtown. He also joined the American Legion and the Swedish Club, where he held court with colleagues and clients alike and often hosted large banquets for them.

As much as he loved eating out, he was an equally accomplished cook who enjoyed inviting people over for his memorable Italian dishes, which he had learned to cook from his mother. This was quite a godsend for all concerned, as Alice was uninterested in cooking and gladly relinquished kitchen duties to her gourmet husband while she used her artistic talents to decorate their home lavishly and create elegant table settings. The house overflowed with family and guests on holidays. Thanksgiving, in particular, called for Ralph’s signature turkey with a rich dressing of mascarpone and other Italian cheeses, Genoa salami, golden raisins, and pine nuts. His daughter-in-law, Angelina Ciliberto Schiavon (my Uncle Tom’s wife – and my godmother), once remarked that on these occasions, it was hard to tell by evening’s end which was more stuffed – the turkey or the guests.

|

My precious mother and grandparents, Joan, Alice, and

Ralph Schiavon, Chicago, Illinois, early 1960s. |

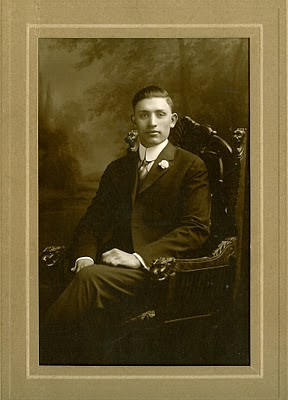

One day in 1954, a handsome young man walked through the door of Alice and Joan’s shop to buy a birthday card for his mother back in Mexico City. He and his landlady had been out shopping, and the landlady, having met Joan Schiavon on a previous visit to the store, dared the young man to go inside to ask her for help. He and Joan were immediately attracted to one another and began taking long walks around the block together. Walks turned into movies and dinners, and the young couple’s relationship deepened into love.

My grandfather, still protective of his daughter, was not happy when the young man, Gilbert Huesca, came to the house to ask him for Joan’s hand on the Fourth of July, her birthday. He had assumed his daughter would marry an Italian, just as her brother Tom had a few years earlier. He looked down sternly at Gil. “Do you have any insanity in your family?” he asked.

The man who would become my father looked squarely back. “No,” he smiled. “Do you?”

Ralph knew he had met his match. Had he remembered that he, too, had married a non-Italian? He gave his permission and began planning a large wedding with a guest list that would fill the church with family and all his clients and professional contacts.

|

Gilbert and Joan Huesca in their first apartment,

Chicago, November 1, 1954. |

My mother, who had wanted an intimate wedding, proved equally as willful as her father. She and my father eloped one afternoon during his lunch break. The date was August 19, 1954. That evening they sent a telegram to Ralph and Alice, who were vacationing in Florida. Though they must have been surprised by the news, they took it graciously and sent the happy couple a lovely floral arrangement with their congratulations and best wishes.

In 1959, Ralph and Alice bought a two-story residence at 7123 South Luella Avenue. They moved into the upstairs flat and invited my parents to move our family into the flat below. I was fairly young at the time, but I recall being greeted on moving day with a marvelous swing and slide set in the backyard, along with a yellow rectangular wading pool for my sisters and me.

Ralph kept his lawns in pristine condition. Both front and back lawns were bordered by tidy boxwood shrubs and colorful flowerbeds of snapdragons, roses, petunias, geraniums, irises, gladiolas, lilies of the valley, and birds-of-paradise (my grandmother’s favorite flower). He also had an herb garden with sweet basil, Italian parsley, and oregano that he used in his wonderful Italian dishes. He was always telling us to keep off the grass, yet he seemed to understand that as children, we needed to run and play, and he indulged us in the way that only a loving grandfather could.

My grandparents doted on our cousins and us. They bought my sisters and me a large Swiss-made child-size surrey with a pink-and-white fringe on top that seated four. We used to pedal it down the block or to the park with our parents or lead neighborhood parades on Flag Day and the Fourth of July. Though he was not one to fuss over children, Ralph loved each of us, his grandchildren, dearly. His letters to my mother during the last decade of his life reflected his pride in all eight of us as we grew into young men and women.

|

My grandparents, Alice and Ralph Schiavon, with me (at age 1),

at my parent’s apartment, Chicago, Thanksgiving 1956.

|

I vividly remember one Sunday afternoon, when I ran upstairs after Mass to visit my grandparents. My Nana Alice, who had been ill with complications from insulin-dependent diabetes, was napping, and my grandfather was sitting in his big leather club chair in the den. He was watching a Chicago Cubs baseball game on TV and listening to a Notre Dame ball game on a small transistor radio he had up to his ear. He motioned me to come in, and I clambered onto his lap.

We sat there, he and I, in awkward silence together for quite some time, he puffing occasionally on his cigar and I wondering what to say to him. Unlike Nana, who could be the consummate playmate to her grandchildren, my Baba (that was the closest I could come to as a little girl to saying the Italian word Babbo, or Grandpa) was not easy to talk to, and at seven years old, I really didn’t understand why. What I did understand in some obscure way was that even on the lap of that silent, enigmatic man, I felt safe and loved.

Copyright © 2011 Linda Huesca Tully

NEXT: Part Four – Twilight

Like this:

Like Loading...

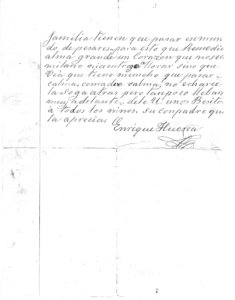

+Huesca,+Eduardo+Huesca,+Cayetano+Huesca,+and+Enrique+Huesca,+Orizaba+ca+1912-1913.jpg)

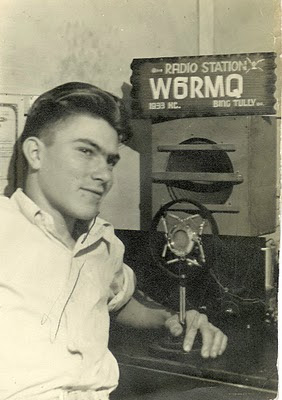

+Tully+in+front+of+his+radio+stationW6MRQ,+137+S.+Grande+Vista+Ave,+Los+Angeles,+ph.+9213765.jpg)