Alice Gaffney (McGinnis) Schiavon

Born June 14, 1895, in Conneaut, Ohio

Died January 1, 1963, in Chicago, Illinois

My beloved grandmother, Alice (McGinnis) Schiavon, was a bit of a rebel.

Charming, but a rebel nonetheless. As a child, she did not want to go to school. She would line up in the morning with her classmates at St. Mary’s School and wait for them to process into class, and then she would walk in the opposite direction toward a nearby field, where she would play with her dolls, returning home at the end of the school day.

This continued on and off for several years. When she was about 12, Alice visited cousins in Cleveland, Ohio, for a couple of months. When her aunt asked her what grade she was in, Alice realized that she was not sure. She would say years later that “the jig was up.” She decided to attend eighth grade with her cousin and surprised herself when she proved to be a good student. She returned to her home in Conneaut, Ohio, and successfully completed the year at St.Mary’s. The picture below shows her with her class at St. Mary’s High School, bottom row, far right.

-+St.+Mary%27s+High+School.Conneaut+Ohio.jpg)

Alice was the youngest of four children born to Thomas “Tom” Eugene and Mary Jane “Janie” (Gaffney) McGinnis. Tom was a New York City native who ran away to sea following the deaths of his own parents. After years of traveling the world as a sailor, he returned to the United States and went to work on the Nickel Plate Railroad in Conneaut, Ohio, where he met and married Janie. Tom, Janie, and their children, Benita, John, Eugene, and Alice lived at 78 Mill Street in Conneaut.

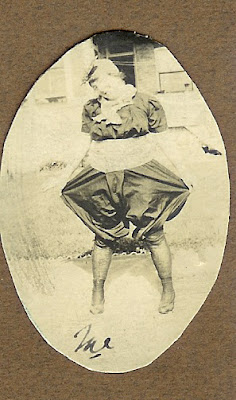

Alice Gaffney was born on Flag Day, June 14, 1895, in Conneaut and was baptized at St. Mary’s Church. She was a sweet and beautiful little girl with soft blue eyes, long bright red hair, and a merry, freckled face. She had a playful imagination and was a free spirit like her adventurer father. Much to her dismay, her fair Irish looks earned her the name of “Carrot Top,” and she spent many an hour hiding in a fire lookout tower with her brother Gene, playing with her dolls until the other children went home.

Around the turn of the century, the McGinnis family moved from Conneaut to Chicago, Illinois, where they lived in a house on Drexel Avenue. Alice met her future husband, Ralph Schiavon, while he was stationed at Great Lakes Naval Station in Chicago. They began a long-distance courtship through the mail, and in one letter Ralph shared with Alice his dream of one day owning his own general store so that they would have enough money to get married and have a family. +Schiavon+-+Wedding+Day,+June+21,+1924,+Chicago,+Illinois.jpg)

He needn’t have worried. After all, Alice, being of Irish descent, certainly already had experienced her share of anti-Irish prejudice. She eagerly wrote back that it didn’t matter where he was from. She loved Ralph and would marry him gladly. The couple were married on June 21, 1923, at St. Joachim’s Church in Chicago. Here they are on their wedding day.

Ralph and Alice had two children, Tom and Joan (my mother). They lived on St. Lawrence Avenue, in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, not far from the McGinnis home. Ralph never did open the little neighborhood store he dreamed of but instead became a tax counselor in private practice. Alice, never one to follow tradition, instead preferred to set her own rules. Unlike most women of her day who stayed home and were model cooks and homemakers, my grandmother disliked housework and cooking and instead loved embroidering, crafting things, collecting stamps and dolls and involving herself in volunteer activities. She used to teach me how to work with yarn, pipecleaners, and beads. Her knack for making the most wonderful things from virtually nothing made her the most magical person in my eyes. She had a special drawer in her kitchen in which she kept small toys that she would give her grandchildren when they would come to visit.She valued her stamps highly. One day she was heading home with some newly acquired stamps in her purse when she was mugged by a would-be robber who knocked her to the ground and grabbed her purse. Determined she would not lose her precious stamps, Alice grabbed the thug’s ankle and sank her teeth into it, holding on tightly. The man screamed, dropped the purse and ran, practically falling into the arms of a policeman who had heard the commotion. The story made the Chicago papers, which praised Alice for her spunk.

Diagnosed with insulin-dependent diabetes in about 1936, my grandmother, who we called Nana, was told by the doctors that she would probably live another two years. She was determined not to succumb to their prediction but instead became even more active, and she parlayed her childhood love of dolls into a passionate hobby, collecting over 500 antique dolls and becoming a national authority on doll collecting. She founded the Alice Schiavon Antique Doll Club and also published Chatter, a magazine about hobbies and doll collecting. Alice’s determination paid off, and she would go on to live for another 37 years, outliving her own doctors.

She loved beautiful things, and she was well-known for her exquisite taste in fine European antiques. Despite her dislike of cooking, she knew how to set an elegant yet gracious table, and she decorated her home with brocades, lace, silver, porcelain, and objets d’art. With my grandfather’s encouragement, she and my mother opened an antique gallery on Chicago’s South Side and traveled to Europe in search of antiques to fill it. (Here she is with my mother, Joan Schiavon, on September 2, 1950, on the Rhone Glacier). My mother used to joke that my grandmother was her own best customer.

She loved beautiful things, and she was well-known for her exquisite taste in fine European antiques. Despite her dislike of cooking, she knew how to set an elegant yet gracious table, and she decorated her home with brocades, lace, silver, porcelain, and objets d’art. With my grandfather’s encouragement, she and my mother opened an antique gallery on Chicago’s South Side and traveled to Europe in search of antiques to fill it. (Here she is with my mother, Joan Schiavon, on September 2, 1950, on the Rhone Glacier). My mother used to joke that my grandmother was her own best customer.

She also had a passion for driving and was pulled over more than a few times for speeding. On one occasion, she rolled down her window and regarded the young officer with her motherly eyes, smiling sweetly, as he told her that he had tried to pull her over but she had kept right on going. “Well, Officer,” she said, “how could that be? Why, with those handsome eyes of yours, I would have stopped on a dime!” He laughed and let her go on her way.

Another time, she was stopped for making an illegal left turn. “The sign says ‘No Left Turn,’ Ma’am,” the officer said to her. “You can’t turn there.” Nana smiled triumphantly. “Well, sir, I did, didn’t I?”

When I was about four years old, my parents moved our family to a two-flat brick house in Chicago, owned by my grandparents. One day I went upstairs to visit my grandparents and learned that Nana was awaiting her hairdresser, who came to the house regularly to wash and set her hair, as Nana was now blind and couldn’t get out of the house easily any more. I must have been about 4 years old. I told her that I would be happy to do her hair for her. Well, she was so thrilled that she called her hairdresser immediately and cancelled her appointment, explaining that her granddaughter would take over that day. We were in my grandfather’s darkly paneled den. My grandmother put the phone down and felt for my hand. “Go ahead, dear,” she directed.

I went to work, lathering up her hair and loving the sudsy sound it made when it was wet. “Oh, this feels wonderful!” Nana said, touching her hair. “It’s so soft. I don’t think I’ll ever need to call anyone else to wash my hair again. I’ll just have you do it all the time.” I stood a little taller and proudly continued lathering.

“By the way, what kind of shampoo are you using?” Nana asked. “Spit,” I answered matter-of-factly. “What was that, again?” Nana asked, trying to hear my little voice. “Spit,” I repeated, a little louder. Silence. “I had to get your hair wet, so I’m spitting into it, Nana!” I said matter-of-factly.

I summoned up my child-like imagination, looked into the rose again, and this time I saw the parade: funny little bugs in uniform, marching about, waving their batons up and down, playing snappy music, cheered on by a miniature crowd. Since then, I have never been able to look at rose without seeing a parade of joy inside it, thanks to Nana.

Her favorite song was the Irish “Danny Boy,” and her favorite flower was the Bird of Paradise.

Alice Gaffney McGinnis Schiavon died shortly after midnight on New Year’s Day, 1963. She left her beloved husband Ralph, her two children, eight grandchildren, and a legion of admirers with a lifetime of memories of a lady who found great joy in life.

HI! this is Ginny Geitner Eakin and I'd love to subscribe or join your blog about our Gaffney, etc family!!!

Remember me???

Ginny Geitner Eakin

in PA