“The first cases (of yellow fever) in Orizaba were all of persons living in a small radius, close around the railroad station. In the next epidemic they spread out a few hundred yards farther and took in another block of houses a little farther off from the railroad station as a center, and it may be that in course of time they will establish themselves permanently a little farther off from the railroad station. But at any rate that point, at Orizaba, is the highest point where I found the Stegomyia mosquito permanently breeding in the country of Mexico.”

– Dr. L.O. Howard, chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Entomology, reporting his findings on the initial outbreak of yellow fever in Orizaba, Veracruz, Mexico, during 1899, Transactions of the Second International Sanitary Convention of the American Republics, The Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C., October 9 – 14, 1905.

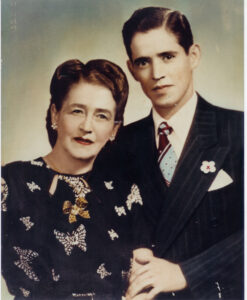

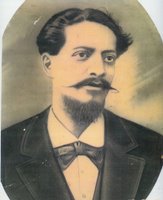

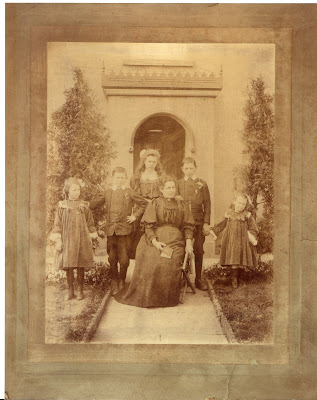

My great-grandfather, Ramón Carlos Francisco (called Francisco) Perrotín (seen here with his wife, Maria Amaro, their son, Francisco, and infant daughter, Catalina), was one of those “first cases.” A mechanic at the railroad station in Orizaba, in Veracruz state, Mexico, he was likely bitten by an infected Stegomyia fasciata mosquito as he worked on one of the engines there. He was pronounced dead at his home on San Cristóbal Street in Orizaba on Saturday, November 11, 1899, at 6:00 p.m., by Dr. Rafael Labardini, the Perrotin (and later Huesca) family physician. He was 32 years old.

A search for answers

The initial outbreak in Orizaba stunned scientists, as the offending species was not native to a city that rose 4,500 feet above sea level. Scientists and medical experts on the disease quickly descended on the area and traced the source of the disease to the mosquitoes breeding in the waste water from the Montezuma brewery, acr.oss the street from the railroad station in the port city of Veracruz. According to Dr. Narciso del Río, a top Mexican public health expert in 1903, mosquitoes were believed to have been transported inadvertently on the trains to Mexico City. They were released when the cars were unloaded at Orizaba, accounting for the first wave of cases at and around that unfortunate station.

Yellow fever was the scourge of the late nineteenth century along the east coast of Mexico, the Caribbean, and several port cities in the United States and Central and South America. After a 3 – 6 day incubation period, victims suffered fever, headache, chills, jaundice and vomiting. Most people survived this first stage, while a fifth of those afflicted were doomed to die in misery, experiencing multiple organ failure, internal bleeding, delirium and coma. The vomit, which took on the consistency of coffee grounds (when it was in fact coagulated blood), gave the condition its Mexican name of El Vómito Negro – the Black Vomit. It might as well have been the plague for the terror it wrought in those days.

Although the modern-day world has seen a significant decrease in cases of yellow fever thanks to the wonders of vaccines, there still is no cure for it. Modern-day treatment for the disease includes offering the patient plenty of rest and fluids, blood transfusions for severe bleeding, and dialysis in the event of kidney failure.

From pot-maker to boiler-maker

If Francisco Perrotin’s demise was dramatic, so too, were his beginnings. We can trace the Pérotin (the original spelling) family back to Melle, an ancient rural town in the region of Deux-Sevres in western France. It was rumored that his grandfather, Jacques Pérotin, had served with the Napoleonic Army. Francisco’s father, Charles Jacques François, however, had been exempted from obligatory military service. In his early 30s, Charles and his brothers, Hilaire and Romain Paul, left Melle for America.

They arrived in Cuba during the last stages of the Industrial Revolution. The sons of a long line of chaudronniers / poeliers, or oven and pot makers, the Pérotin brothers were hard-working, ambitious, and creative. They became entrepreneurs, building stoves and ovens and figuring out how to use their metal-working skills in new ways.

By 1860, Charles, now known as François, had moved to Shreveport and married Catherine Grady, a young Irish seamstress who had sailed to America with her own sister some years earlier. The couple lived in Shreveport for a time before moving to Orizaba to make their mark on the flourishing railroad enterprise being promoted between Veracruz and Mexico City.

A new venture

Shortly after arriving in Orizaba, Catherine gave birth to María Dolores on September 15, 1866. Francisco was born there two years later, on August 30, 1868, and a younger brother, Ricardo, was born on Mach 31, 1899.

Buoyed by the high tropical climate, where the air was pure and everything flourished, Francisco grew into a strong young man who followed in his father’s footsteps as a railroad engine mechanic.

Thanks to François’ keen instinct for opportunity, the family was financially comfortable and well-traveled. María Dolores married a British train driver, Timothy Bennett, at a celebrated wedding at the Orizaba train station in 1885, and Francisco married María Amaro in 1889. He was 20 years old at the time; María was 18. The couple welcomed their first-born son, Felix Francisco Benjamin (nicknamed “Pancho”), a year later. Four other children followed: Juan Carlos, Catalina (my grandmother, or Abuelita, who was named for her own Irish grandmother, Catherine), Hugo Ramiro, and Blanca Luz.

Francisco, María, and their young family lived in a house on the “with the letter ‘I’ on the second street of San Cristobal” in Orizaba. As María was also multilingual, they spoke Spanish, French, and English at home, so the children grew up speaking all three languages fluently and gliding easily from one to another, much as their parents had done before them.

María Dolores and Timothy moved to England sometime between late 1890 and early 1891 with a young son. François died of meningitis in 1891 at his home on the station property. A year later, Francisco and María’s infant son, Juan, died of the same disease while still in his infancy.

Catherine, also grieving for her beloved François and missing her daughter, eventually decided to join her and her son-in-law in England. Though she hated to leave her son and grandchildren, she told herself that Francisco was going to be all right with his young and growing family. Dolores, in a new land, needed her mother more.

Catherine left for England in 1895. As she bade Francisco farewell, she may have wondered whether she would live long enough to see him and his family again. Little did she know that she would outlive her son by a mere two years.

When Francisco died in 1899, Pancho was 9; Catalina was 6; Hugo was 4; and Blanca Luz (later called Blanca) was a month shy of her first birthday. Juan had died seven years before of meningitis. María, Francisco’s wife, was pregnant with their sixth child.

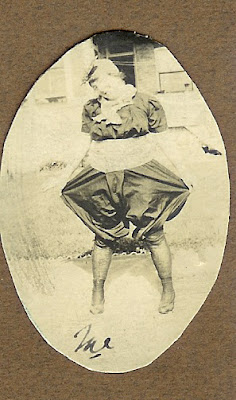

That sixth child, Roberto, would be born sometime between January and February of 1900. Of the six children, he would be the shortest-lived, succumbing to infantile cholera at the age of nine months the following November, while Catalina (pictured below, left) would live the longest, dying in 1998 at the age of 105.

My father, Gilbert Huesca, recalled that his Uncle Pancho had very Irish looks – a stocky build, red hair, and fair skin. He also remembered that his uncle owned a most unusual cast iron stove, atypical of the stoves in Orizaba at the time. Did Pancho build it? Or did his grandfather, Francois, the poelier?

Family bond interrupted

Hugo, like his father and grandfather, worked for the Mexican Railroad in the port city of Veracruz. Afflicted with epilepsy, he became the family correspondent with his Aunt Dolores Bennett and his cousins overseas. When his letters stopped suddenly that spring, coincidentally following a major earthquake in Mexico, the Bennett family erroneously assumed that he and all the rest of the Perrotin family in Mexico had been killed in the earthquake. In fact, Hugo had died of his disease in Veracruz on May 13, 1920. He was 25 years old and unmarried.

Contact between the two branches of the family resumed a century later, when Don and Jennie Murray of Highnam, England, contacted me and began correspondence, in June 2006.

The Perrotin-Amaro women had wavy dark brown hair and lively brown eyes, and they possessed an inner strength that was as appealing as their beauty. Blanca Perrotin was about 5’6”, slender, regal, proud, strong-willed, and beautiful. As a young woman, she was the image of her grandmother, Catherine, and perhaps because of this, she felt extremely close to her all her life, though Catherine had left Orizaba three years before Blanca was born. She was married briefly, but when she found out that her husband had a temper and was known to sleep with a dagger strapped to his calf, she either separated from or divorced him immediately and resolved never to marry again. Life had not turned out the way she had hoped, but she devoted herself to her widowed mother and was kind and loving to her nieces and nephews. Her stern personality was quite a contrast to her sister Catalina, a happy person always surrounded by a loving husband and 11 doting children.

María Amaro Perrotin, Francisco’s widow (shown above), lived to age 98. A beautiful and attractive woman, she would marry again, twice in fact, after Francisco’s death, to foreigners; both of whom died of natural causes. She ran a bakery or café in Orizaba, helped by her daughters. It was there that Catalina met the young Cayetano Huesca, who she would soon marry.

Postscript: Revenge

My husband and I have been sick since last week with nasty colds – it is very damp here in California right now – and we’ve spent a considerable amount of time resting and reading. Last Saturday, I read up on yellow fever (not the best topic to tackle when you’re sick, by the way) and learned a considerable amount about Stegomyia fasciata, the species of mosquito that became infected and went on to spread the disease throughout coastal Mexico and beyond. It must have really made an impression on me, because when I went to bed that night, I had vivid dreams about mosquitoes and yellow fever.

Sometime during the middle of the night, our eldest son tapped on our door to ask where the bug spray was. It seemed that there was what he called a “gi-normous bug” flying around outside our bedroom, on the upstairs landing. Our son tapped again on our door a few minutes later and said he couldn’t find the bug spray and was going to leave the bug there.

Now, normally one of us (not me, mind you) would have gotten up at that point to take care of the dreaded intruder, but my husband and I were too sick and too out of it to budge. Still, I knew what was out there and spent the rest of the night in restless sleep, terrified of being bitten by that horrible mosquito and getting West Nile Virus or some other blood-borne disease. Funny how one’s mind can take off like that! When I awoke in the morning, I rolled up a nearby magazine, gingerly opened the door, and held my breath as I looked about the landing. There it was, just above the bathroom door.

“Damn you!” I yelled at him as I swatted it violently. I startled myself with my own reaction and then realized I had killed it not just for myself but for Francisco and the family he left behind. Looking at its flat, lifeless form on the magazine, it seemed ironic to think that such a small insect could have inflicted so much misery.

I went back to bed and slept quite well.

Updated October 15, 2023.

Copyright (C) 2019 Linda Huesca Tully

.

-+St.+Mary%27s+High+School.Conneaut+Ohio.jpg)

+Schiavon+-+Wedding+Day,+June+21,+1924,+Chicago,+Illinois.jpg)