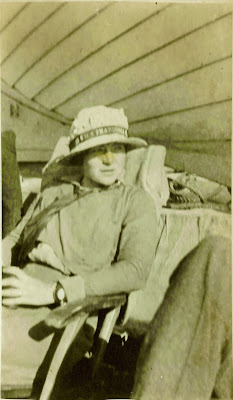

Benita (McGinnis) McCormick

(1889 – 1984)

|

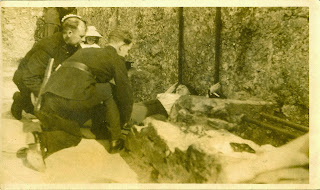

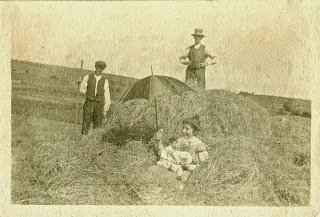

| “Baby Maureen” is the only person we can (partially) identify in these pictures. Here she is, with (possibly) her parents and another man. Might her mother be cousin Bessie Quinn? |

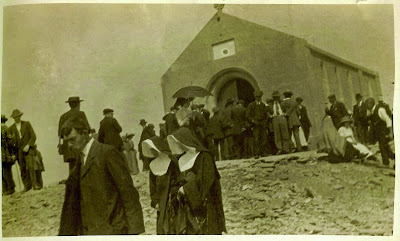

More Mystery Cousins! As with the other photographs we’ve seen recently on this site, these come from my great-aunt Detty’s (Benita McGinnis McCormick) scrapbook pages of her 1913 visit to Ireland. She had a grand time on the “auld sod,” visiting with her Irish cousins, and these photographs show they were quite a playful lot.

|

| Unidentified cousins with Baby Maureen. The man holding her may be her father. The man in the cap appears to be younger – maybe her older brother? |

Unfortunately, as we have seen already, Aunt Detty unwittingly left it to us to figure out just who these lovely people were by not leaving us any identifying information about them.

Our family’s Irish ancestor surnames were McGinnis, Healey, Kelly, Gaffney, and Quinn. Because Benita’s father, Thomas Eugene McGinnis, lost his parents when he was a small child, he might not have known much about his relatives in Ireland (where his father is said to be born) or in Scotland (his mother’s birthplace, according to some census records). For this reason, I would be less inclined to think any of these people were McGinnises, though I would not rule it out entirely.

|

| Aunt Detty captioned this, “Baby Maureen and Nurse.” Was the nurse a nanny, or one of the nurses from Mountjoy Prison hospital? |

I know nothing about the Healeys and the Kellys, except that they are ancestors of the Gaffneys and the Quinns, respectively. As noted previously, we have a picture of Benita’s cousin, Eileen Kelly, with the McGinnis family in their Chicago home in 1919.

I am fairly certain Eileen traveled with Benita to Europe, as her name appears on the ship’s manifest back to America. Hence, we have another hint that the Gaffney-McGinnis family kept ties with their Kelly relatives in the U.S. and maybe back in Ireland. That could make the Kelly branch another possibility for these pictures, though Eileen will have to await her turn patiently while I try to confirm her family connection at a later date. So many relatives, so little time!

While Benita’s father’s family seems a remote possibility for the “surname photo match game” we are playing with these unidentified photos, her mother’s (Mary Jane Gaffney) family might be more likely candidates. Take her maternal grandfather’s side, the Gaffneys, for example. Most, if not all, of Benita’s Irish grand uncles and grand aunts had settled in the midwest and kept close contact with one another. It would make sense that they also kept their ties to their extended family back in Ireland.

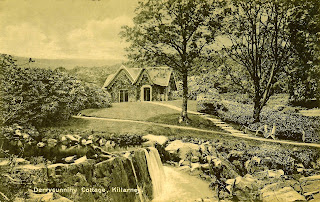

Benita’s maternal grandmother’s family, the Quinns, pose a stronger possibility. Take a look at the picture postcard below This postcard did not belong to Aunt Detty but to her younger sister, Alice (McGinnis) Schiavon, my maternal grandmother.

|

| Picture Postcard of “Grandpa” Quinn and Lilly the old driving horse. The location, somewhere in Ireland, is unknown. |

The dedication on the back of this postcard reads,

|

| Cousins? |

|

|

Cherubic Baby Maureen and nurse. |

************

Copyright © 2014 Linda Huesca Tully