Benita Elizabeth (McGinnis) McCormick

|

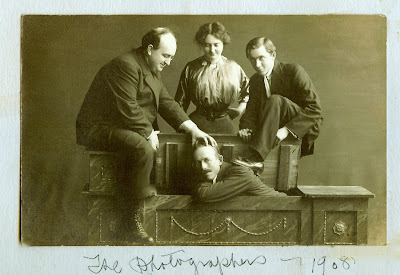

| Benita McGinnis, Chicago, Illinois, circa 1910 |

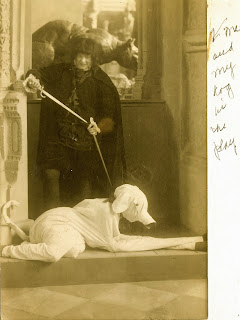

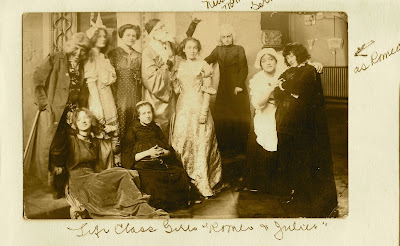

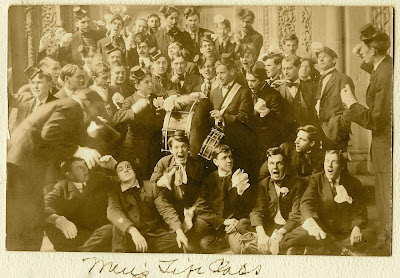

Passionate about art, my grand aunt Benita McGinnis had shown promise as a young artist. When she was still in her mid-teens, she was admitted to the prestigious School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early years of the 20th century. She was vibrant and outgoing and proved herself a natural leader from the time she entered the Art Institute, often appearing at the center of school photographs, surrounded by her laughing classmates and friends.

She made friends easily and had no trouble striking up conversations with both students and teachers. But there was one exception.

During her first year at the Art Institute, there was a slightly older girl, maybe two years ahead of her, in the Life Drawing class. Benita had seen her several times, even tried saying hello, but she never got a response. This older student was serious, introspective, and aloof. She dressed differently than most of the students, preferring austere, mostly black clothes to the stylish, bright dresses most girls of the time tended to wear. To the cheery and extroverted Benita, she must have been something of a mysterious challenge.

One day as Benita walked down the long hall to one of her classes, the door to the Life Drawing classroom flew open and the girl bolted out. Sobbing uncontrollably, she practically ran into my grand aunt as she headed for the garden.

Benita felt a surge of sympathy for the girl and wanted to help. She made her way to the garden and found her under a tree in the garden, still crying.

Approaching the older student, my grand aunt asked gently if she could help in some way, but the girl pulled away abruptly. “Just leave me alone!” she lashed out. “Go away!” Confused, Benita left.

She told me this story in 1982, over 75 years later. “We all knew there was just ‘something’ about Georgia, and sure enough, we were right,” she recalled with a grin. “I never did find out what happened that day, because she left the Art Institute right after that incident. But things seem to have worked out for her, haven’t they?”

“Georgia” was Georgia O’Keeffe, and yes, things did work out for her. After leaving the Art Institute, she moved to New York and eventually to New Mexico, establishing herself as one of the most celebrated American artists of the 20th century. Called the “Mother of American Modernism,” she painted bold, visionary, and often startling landscapes and and large-scale renditions of nature and animal bones of New Mexico and the Southwest. Her daring explorations of these simple subjects caused people to experience them in ways they never would have done otherwise.

|

School of the Art Institute of Chicago, 2005.

Courtesy GARNET. Flickr, Creative Commons |

Though I never would have anticipated it at the time, a couple of months after this conversation with my aunt, I, too, had a close encounter with Georgia O’Keeffe. I was working the ticket counter for Continental Airlines at San Francisco International Airport one afternoon when she checked in for the mid-afternoon flight from San Francisco to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

This time, the young woman my aunt had known at the Art Institute was being pushed to the ticket counter in a wheelchair, her aged frail frame wrapped in a thick black shawl. Her face by now was lined with 90+ years of experiences, and her fine gray hair was severely tied up at the nape of her neck. Though heads occasionally turned as they recognized the legendary painter, she stared straight ahead, her lips tightly pursed, seemingly indifferent to the chaos around her. I had no idea that by now she was almost completely blind.

Some of my co-workers whispered quietly as they recognized this artistic icon of American Modernism and stole admiring glances at her. I was tempted to ask her if everything was all right, or whether there was anything else we could do for her. But I had a feeling I knew how she would react. I handed her a first class boarding pass, wished her a good flight home, and left her alone to her thoughts.

**********

Copyright © 2013 Linda Huesca Tully

Like this:

Like Loading...