The Carpenter of Mission San Jose

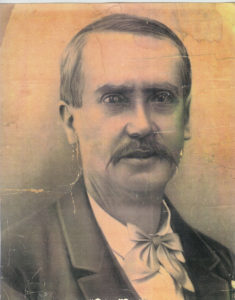

Joseph Edouard Baron (1825 – 1921) *

If you’ve ever explored your family tree, you’ve probably stumbled across someone who left few to no breadcrumbs on the ancestry trail. Maybe you gave up your search, or you were content to have just found their name as a link to someone else who was, shall we say, a bit more intriguing.

For me, such was the case with Eduard Baron*, my husband’s great-great-grandfather. Gradually, though, the mystery of how he was connected to Mission San Jose led me back to the archives at Santa Clara University to learn more about him.

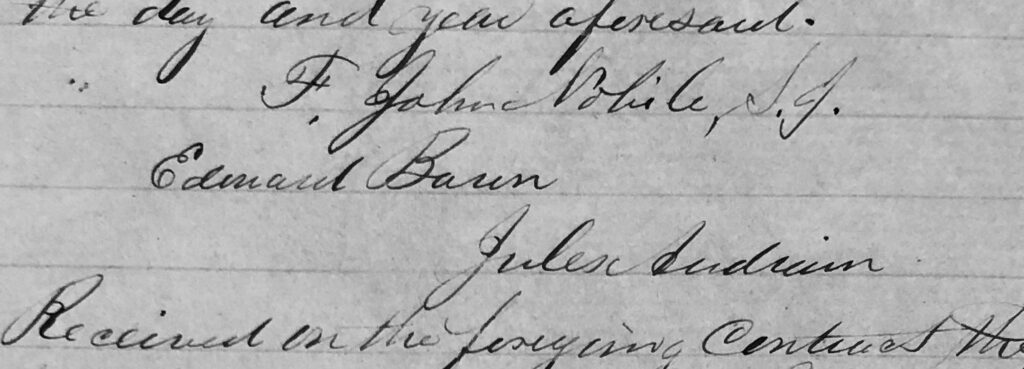

It had been thrilling to see Eduard’s signature, but the document he signed was a legal settlement that left more questions than answers. Dated July 22, 1852, it also was signed by Jules Audrain and Father John Nobili, a priest of the Society of Jesus, who was acting on behalf of the Bishop of Alta and Baja California.

So what brought Eduard and Jules to Mission San Jose, and what kind of work did they do there? Had Nobili hired them?

I returned on a cold February morning in 2018 to Santa Clara for the answers, poring over correspondence and documents from the Papers of John Nobili, S.J., a part of the Inventory of Presidents’ Papers. Most of the letters were in Spanish or French, with a very few in English and one in Latin. They were about a little-known episode at Mission San Jose that had involved my husband’s great-great-grandfather, Eduard Baron. But how? It would take far more than a single afternoon to study and analyze the information.

With the archivist’s permission, I photographed some 43 documents and went home to read and translate many of them into English, a task that took a couple of months to do in between family life and a hectic work schedule. As I pieced together the bits of information I already had on Eduard and the events mentioned in the Santa Clara documents, a clearer picture of him and his story began to emerge.

Between 1850 and 1851, Eduard Baron had to admit that the long journey from his native France to California in search of gold had not gone as he expected. He had left his family in 1848, sailing across the Atlantic Ocean and traveling overland to the West Coast, one of tens of thousands of immigrants who hoped to strike it rich in the gold fields of California.

Although some of the Argonauts struck it rich in the Sierras, most were not so lucky. Some, broke and broken by their fruitless efforts, returned to their homelands in dismay. Others, who were more enterprising, if not downright greedy, capitalized on low supply and high demand for everyday necessities and charged exorbitant prices for food and supplies at the rate of whatever amount desperate new arrivals could pay. Still others refused to look back. Pioneers in both spirit and action, they forged their own destinies, finding or creating opportunities and settlements.

Eduard, like many 49ers, likely found little or none of the coveted precious metal during his foray. The only prospecting he faced now was what to do next with his life at the ripe old age of 23.

It did not take him long to realize that there was more money to be had in building new towns and homes to keep up with the influx of settlers arriving daily in California. San Francisco’s own population, at 459 in 1847 when it was known as the town of Yerba Buena, had exploded to 34,000 almost overnight. Sensing his carpentry skills were a lucrative commodity, Eduard made up his mind to return to San Francisco. He was joined by a fellow French expatriate and carpenter, Jules Audrain.

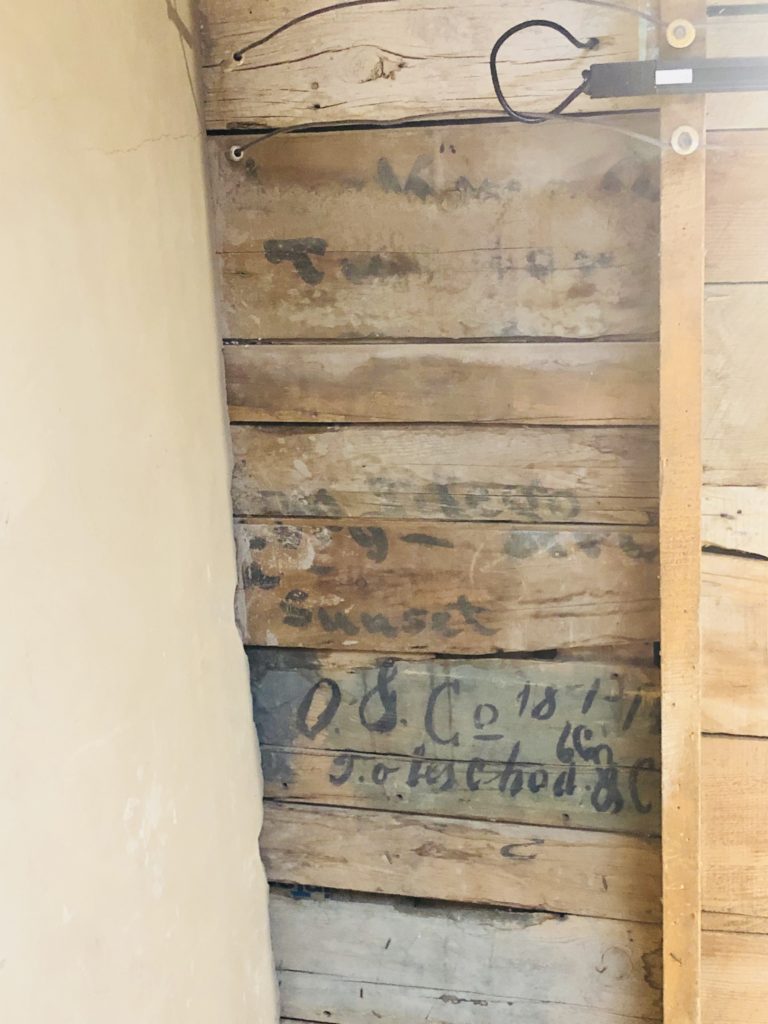

On their way back, they stopped at Mission San Jose, about halfway between the Bay Area and the California gold fields. The town that had sprung up around the mission had become an important trading post and layover point for travelers going to and coming from the gold mines through Mission Pass along the Diablo mountain range. There, they could find lodging at one of two hotels and buy fresh fruit and meat and pelts from the coyote, deer, elk, bears, mountain lions, and cattle roaming the lands.

Overlooking the San Francisco Bay and the lush valleys surrounding it, the growing mission settlement was not a bad place to contemplate the future. The natural beauty of its setting and its mild, Mediterranean-like climate, unlike the changing, sometimes extreme weather of the Sierras and the damp fog and wind of San Francisco, appealed to the two young men, and they chose to go no further. The decision would alter their own lives and the history of the mission.

Header image: Signature page of legal settlement executed on July 22, 1852, by Father John Nobili, S.J., Eduard Baron, and Jules Audrain. Image courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Santa Clara University.

* Note: Historical documents reveal that after arriving in the United States from France in 1849, Joseph Edouard Baron dropped his first name so that he was known as “Eduard, ” a simplified variation of his name that left out the “o” from the French spelling. In Arizonan and Mexican historical documents, his name took on the Spanish version of “Eduardo.” This article uses his preferred name, Eduard.

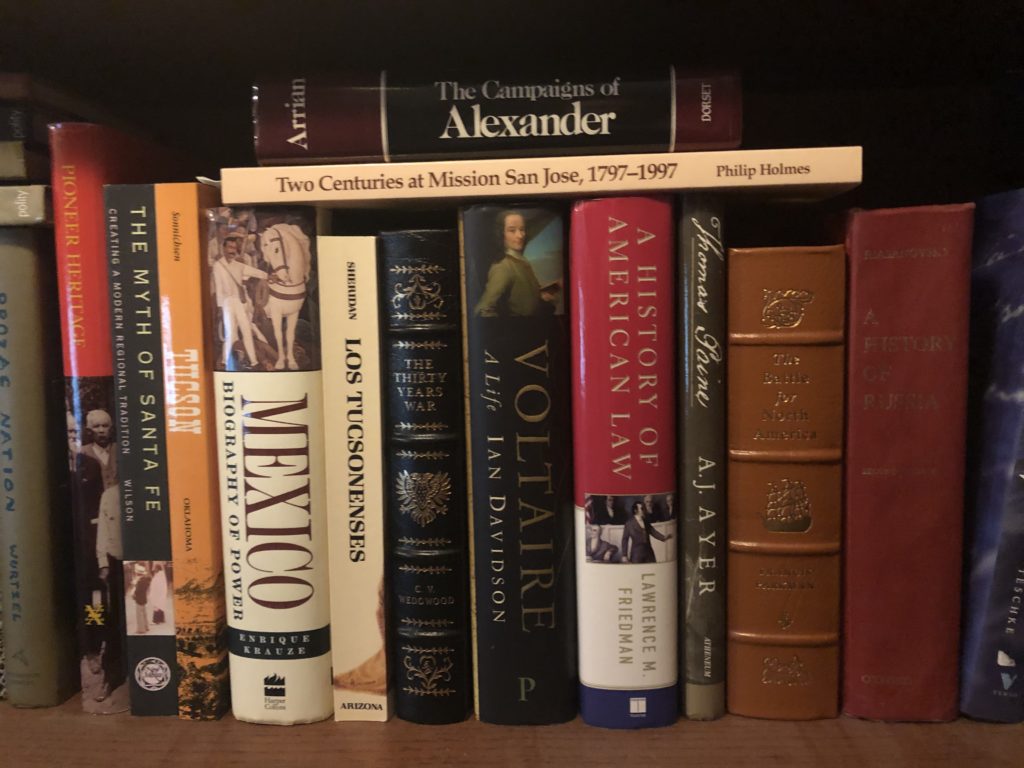

Work Cited

Mission San Jose Business Contract. July 22, 1852. Archives and Special Collections, 3DB01, Papers of John Nobili, S.J. 1851 – 1856, Santa Clara University.

Next: Part 3: A Hard Offer to Refuse

To read all the episodes in this series or to find other stories about the Baron family, click here.

Copyright © 2021 Linda Huesca Tully