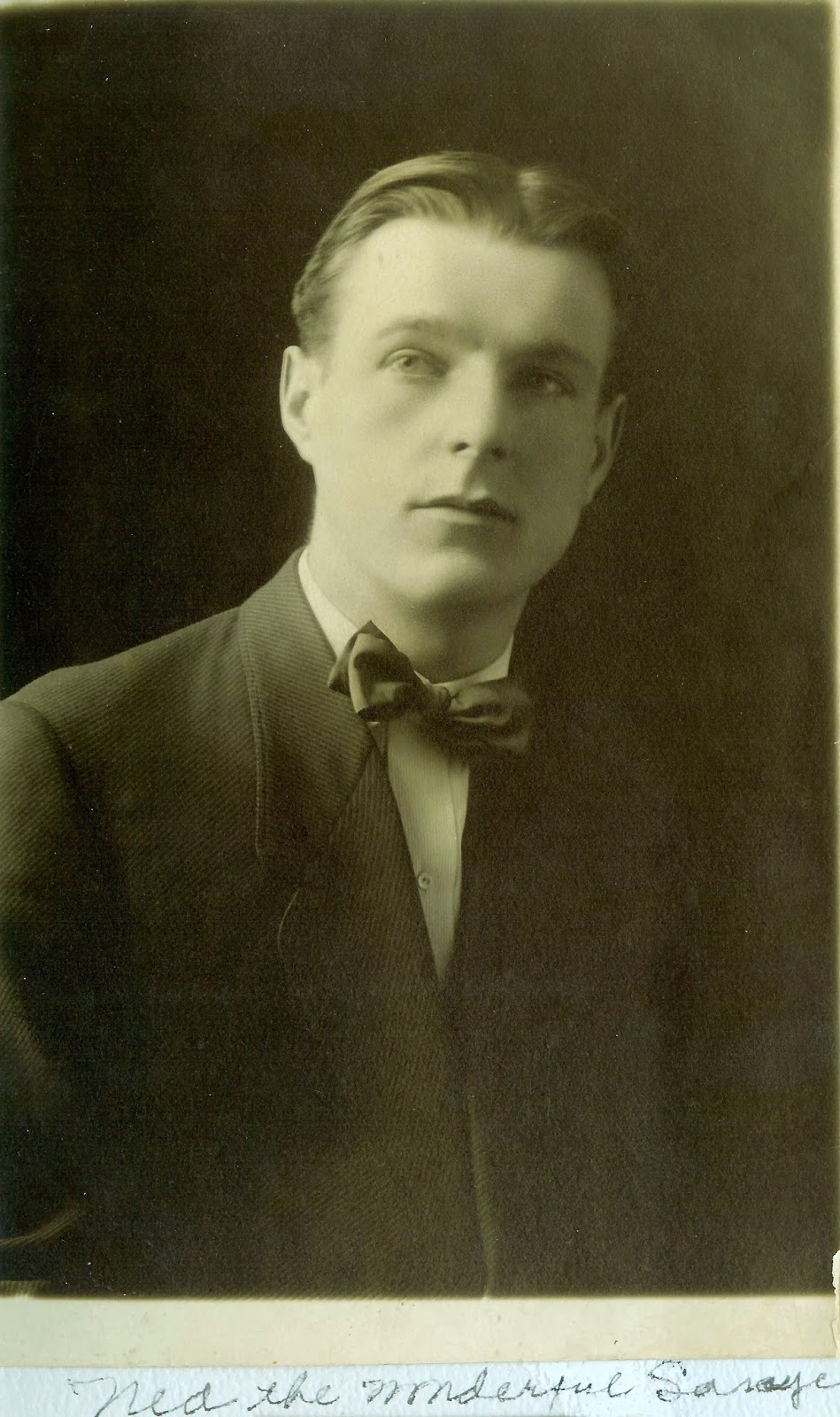

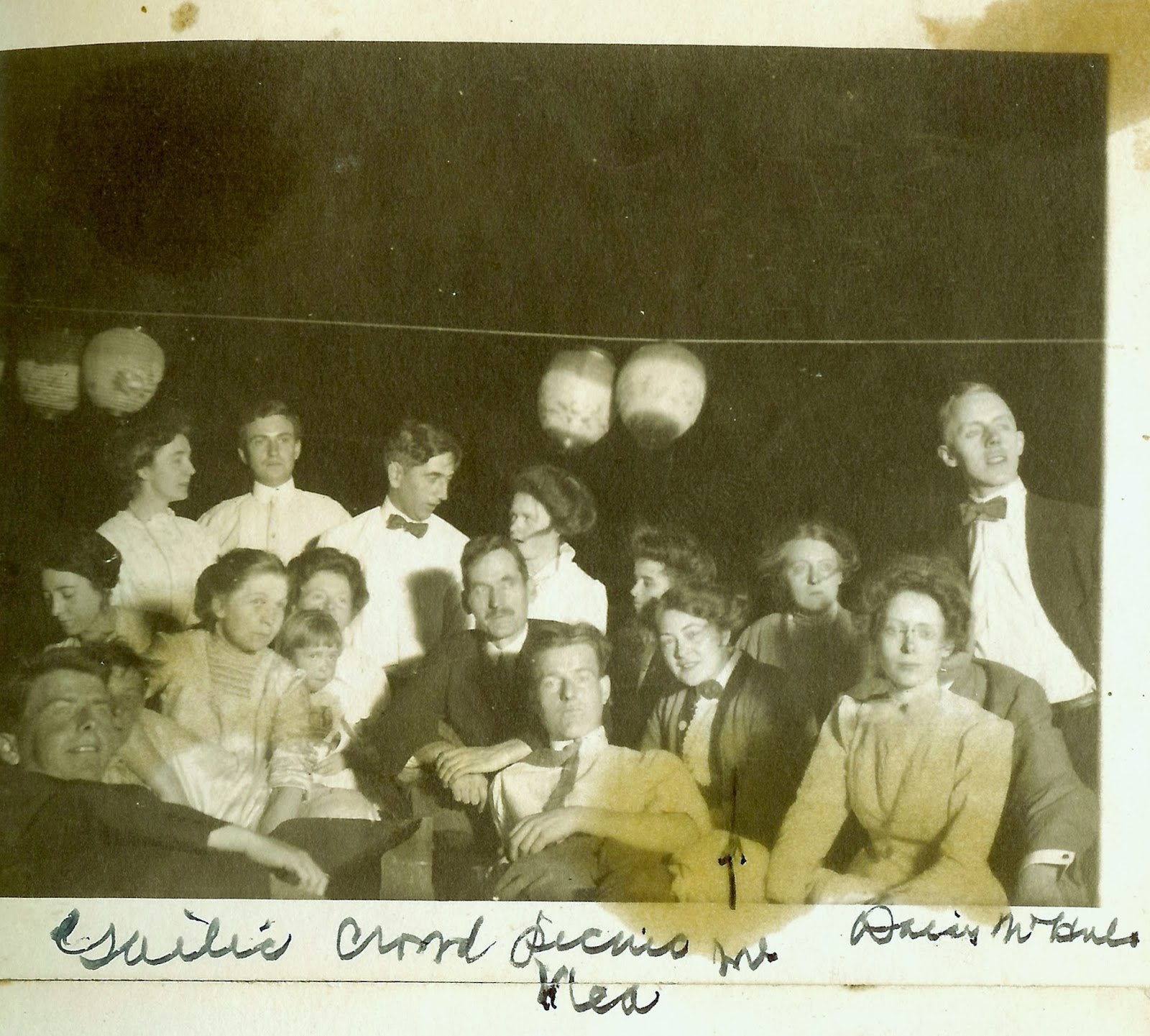

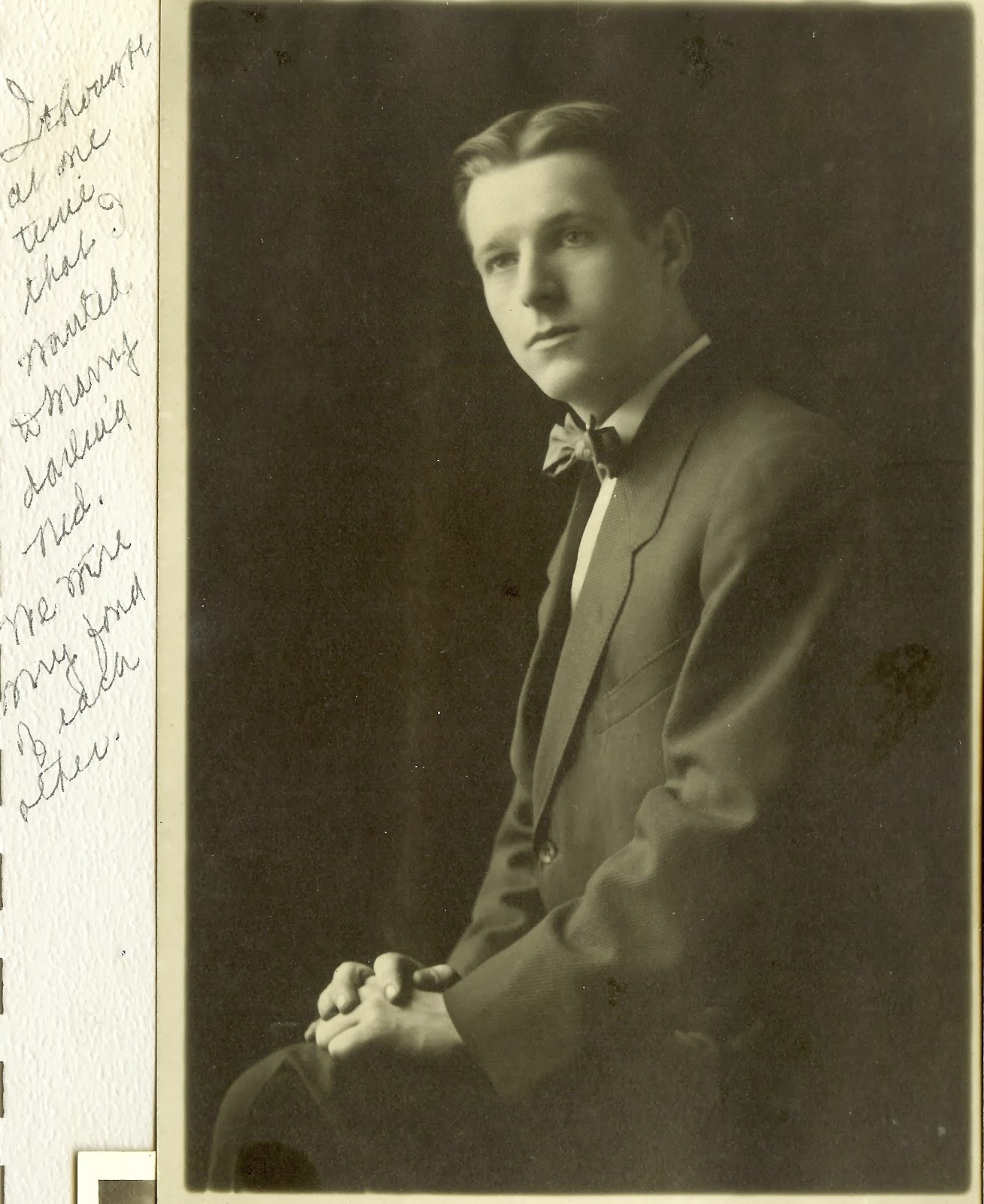

Benita (McGinnis) McCormick

(1889 – 1984)

|

Benita McGinnis, circa 1921.

Chicago, Illinois. From Benita’s scrapbook. |

Benita (McGinnis) McCormick, my great-aunt Detty, was not afraid of a little controversy. In fact, she believed that if you did nothing else in your life, you should always stand up for your convictions, whether or not they were popular.

Sometime around 1915, she applied for and was appointed one of 12 members of the Censor Board of Chicago. The Censor Board was a civil service board, established in 1907 by the Chicago Police Department, as part of its effort to enforce laws and ordinances governing all matters affecting public morals.

Its charge being to protect the sensibilities of the Windy City, the Censor Board reviewed movies to determine their moral suitability. This involved cutting out “any and all objectionable parts of every film submitted to them” that might either be morally offensive or promote delinquency among the public, especially the young.

In a manual for would-be scriptwriters called How to Write for the ‘Movies’, the early movie columnist Louella Parsons explained, “If (a film) is artistic, has educational value, they mark it as excellent; if it contains any objectionable features they order this particular part of the film cut out. If the film is entirely unfit for public exhibition they order it suppressed.” (1)

|

This wire story, from the Associated

Press, quoted Benita, chief of the

Chicago Censor Board, as stating

that “censorship has come to stay.”

The Miami Herald, Sept. 12, 1921. |

Parsons cautioned scriptwriters against using objectionable subjects in films that would render them unfit for public consumption. Among these were the killing of any human being; violent crime; suicide (or the suggestion of such); burglary (if it was depicted outright and not simply suggested); vulgarity, either outright or implied; lynching; malicious mischief; destruction of property; or racially motivated jokes or slurs.

Apparently some movies still managed to slip past the keen eyes of the Chicago Censor Board, most notably D.W. Griffith’s silent movie about the Civil War and Reconstruction, The Birth of a Nation.

In 1915, the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) learned that a permit had been issued for The Birth of a Nation to be shown in Chicago movie houses before it could be submitted to the Censor Board for approval. Citing the movie’s explicit racism and violence, the group convinced the mayor of Chicago to ban the movie.

A Cook County Superior Court judge later reversed the mayor’s decision. By then, the mayor’s move had ignited renewed public debate on censorship. Similar public reaction to bans by other cities spurred high attendance nationwide as thousands of curious viewers flocked to theaters to judge the movie for themselves.

Local women’s groups applauded the Censor Board’s efforts to preserve and promote morality in society. They credited the board with contributing to a dip in juvenile delinquency, racial strife, and violent criminal acts in the city.

Benita became the chief censor of the board and made the national news over the years as she discussed board decisions on various movies. In this 1921 interview with the Associated Press about some of the odder challenges the board dealt with, she made an interesting remark that “censorship has come to stay.”

MOVIE MEN ARE QUEER IN CENSORING FILMS

They Cut Out Things That the Censor Board Approves, and Put in Things That Are Disapproved

CHICAGO, Sept. 9. — When movie men take to censoring their films, they sometimes have some strange ideas, it is related at the Chicago censor board.

Distributors getting a picture they think will not pass the board now and then take a hand at fixing it up. They have cut out funny parts that the censors think great, left in parts that the censors hold thumbs down on, and otherwise perplexed their judges.

“We have sometimes sent back and asked them to give us the whole picture, as we did not find anything wrong in it,” remarked Miss Benita McGinnis, Chicago’s acting chief censor. “At other times we have rejected a whole film after their hopeless attempts to doctor it up.

“The Chicago censors sit as sort of a humane society on the city’s films. They are keenly averse to useless brutality. Their “Cut-out Book” contains frequent injunctions to eliminate scenes in terse terms as these:

“Cut kicking and striking man on floor.”

“Cut slugging man.”

“Cut two close views of choking.”

The number of violent movie deaths in Chicago has been reduced by millions annually since the censor board took a hand in reducing the film murders. They cut them out with a strong hand.

Another aspect of the censors’ work is indicated by this line from the Cut-out Book:

“Cut all scenes of white children chasing negro boy and throwing stones at him.”

An incident like that was credited with starting a race trouble.

Disregarding of the law is another suggestion that the censors try to offset. Glorification of lawlessness on the plains is one of the most frequent forms in which this comes up.

“A censor should be able to put back something as vital as he takes out, only less offensive,” is a principle at the Censor Board.

“We are doing constructive work in censoring today that we did not know could be done seven years ago,” Miss McGinnis said.

“One reason for this betterment is that the moving picture people realize that censorship has come to stay.” (2)

Not everyone agreed with my aunt. Many, including Louella Parsons, acknowledged that while the practice of censorship succeeded in giving the public movies of higher quality, it risked the chance of being too strict and having too much power.

James McQuade, a contributing editor of the publication The Moving Picture World, called the question in 1914 in his Chicago Letter: “How far one set of people shall decide what is proper for another set of people to do; and conversely, how far the second set of people may conduct themselves to suit themselves in violation of the feelings of the first people, is as old as history, and will last as long as the world. . . The public has shown by its withdrawal of patronage that it is eminently qualified to protect its own morals.”

But even he allowed that there were exceptions. “Censorship at all times and of all kinds is dangerous, and can only be permitted to exist when it is exercised with the utmost forbearance and the utmost common sense.”

By 1922, public opinion had swung away from the need for censorship as a way of ensuring quality films, especially as people began to realize they could contribute in their own way to the success or failure of a film simply by voting with their feet. Even more important was growing concern for the protection of First Amendment rights.

This was something that even Benita, now Mrs. Benita McCormick, could not ignore. As firmly as she had believed in the good of censorship during her tenure as Chicago’s chief censor, she also was just as wise and open to reason. As an artist and writer herself, she placed a high value on freedom of speech, in her own subjective way. She began to realize she could no longer condone the work of the Censor Board and made up her mind that it was time for a change.

That year, The Film Daily announced that Benita was quitting the board, of which she was the chief censor. “Mrs. Benita McCormick, chief censor of the Chicago commission, has resigned. Chief of Police Fitzmorris has appointed Edith E. Kerr, Mrs. McCormick’s successor.” (4)

Censorship continued for many years in Chicago, finally coming to an end in 1961. Censor boards eventually gave way to the formation of what would become the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA),

a self-regulating organization not connected with any government agency. In 1968, the MPAA created a ratings system, ostensibly to provide viewers (particularly parents) a way of deciding which movies they should allow their children to watch.

(1) Parsons, Louella Oettinger, How to Write for the Movies, September 1915, A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago.

(2) “Movie Men are Queer in Censoring Films.” Associated Press, as appeared in The Miami Herald, September 12, 1921.

(3) McQuade, James, “Chicago Letter,” The Moving Picture World,

http://books.google.com/books?id=UEs_AAAAYAAJ&q=censor+board#v=snippet&q=censor%20board&f=false

(4) The Film Daily, Vol. XXI, No. 13. July 14, 1922. New York City https://archive.org/stream/filmdaily2122newy/filmdaily2122newy_djvu.txt

************

Copyright © 2014 Linda Huesca Tully

Like this:

Like Loading...