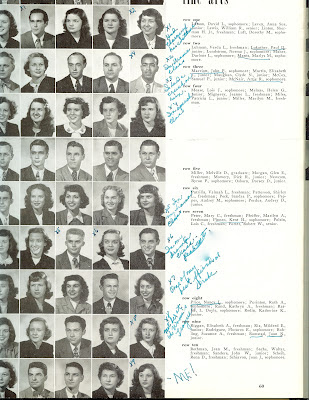

The Very Talented Miss Margaret Yu

|

Margaret Yu, far right, circa 1950. I am not sure where this photo was taken or whether the people with her were family members or friends.

|

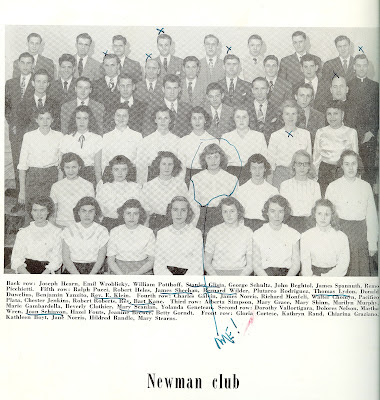

My mother, Joan Joyce (Schiavon) Huesca met Margaret Yu while both were attending Saint Francis College in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Margaret was an exchange student who had studied Linguistics at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and my mother was a drama major. They hit it off instantly and and began a friendship that flourished and deepened over the years until my mother’s death in 1987.

Margaret came from a family of elite professors in Hong Kong. Her parents owned two neighboring houses, one built in Chinese style and the other built in Western style, on a hill overlooking Kowloon. One week the family would live in the Chinese house, speaking Mandarin and observing Chinese customs, and the next week they would move everyone – servants and all – into the Western house next door, where they would speak English and live according to British customs. My mother believed this accounted for Margaret’s flawless English and impeccable manners.

Margaret was a highly cultured lady, having traveled with her parents and brothers and sisters around the world several times. She was well read and spoke several languages fluently, Mandarin, Cantonese, English, German, and French among others. Yet for all her worldliness and sophistication, she loved having fun just as much as the next young woman, and she and my mother spent their free time going to the theater, playing card games, or sipping root beer floats (also called “black cows” in the Midwest) with their classmates at Woolworth’s lunch counter.

Having no family locally, Margaret frequently accompanied my mother on her weekend visits home to Chicago. The two of them would sit cross-legged on my mother’s bed and talk late into the night, sometimes giggling so much that my grandparents, Ralph and Alice (McGinnis) Schiavon would have to knock on the bedroom door to ask them to keep the noise down. Even so, my grandparents loved Margaret and treated her like a special second daughter, allowing her all kinds of indulgences, such as sleeping in late in the morning and running around the house in her bright red Chinese silk pajamas. My grandfather delighted in her effusive compliments on his Italian cooking. At times she would reciprocate the favor, cooking elaborate Chinese dishes for the family.

Once my grandmother walked into the bedroom and found Margaret sitting straight up in bed, eyes closed and motionless. Fearing she might have had had a heart attack, my grandmother shook her, and Margaret awoke with a start. Margaret later explained that the Chinese slept that way because they believed that it would be easier for them to go straight to heaven if they died in their sleep. My grandmother never found out whether this was true or not, but she was quite relieved.

|

Margaret gave my mother this silk

embroidered Chinese purse in about

1948. My mother treasured it and carried it

proudly on special occasions. |

Margaret Yu returned to Hong Kong at the close of the academic year, but she and my mother remained close friends all their lives. They wrote long letters to each other throughout the years, sharing everyday stories of their lives, hopes and dreams.

Margaret’s letters were instantly recognizable. Printing her return address under her name, “Miss Margaret Yu,” she always wrote on aerogrammes,. These were were thin, light blue letter stock, bearing imprinted postage images of Queen Elizabeth II (Hong Kong was still a British colony at that time) and labeled “Par Avion/Via Air Mail” in blue and red type. It was always exciting to see these exotic letters, often featuring red Chinese characters and sometimes even exquisite pre-printed drawings. How thin they were, yet how much news they contained!

My mother would slit the letters open carefully but eventually allowed us the honors as we grew older and more adept at such things. She breathlessly read “Auntie” Margaret’s letters to my father, my sisters and me, as we crowded around her, glued to every word. Through these letters we got a taste of what it was like to live in Hong Kong during a pivotal time of economic and cultural turmoil. As the years passed, we began to feel as though we knew her almost as intimately as my mother did.

We heard about the linguistic classes she taught at the University of Hong Kong and of the books she wrote on the subject. We learned about the rise of factories that made the colony a manufacturing giant in the 60s. We heard harrowing stories of the chaos and riots in mainland China that spilled over into Hong Kong as Chairman Mao Zedong’s Communist Party challenged British rule. Being young children, we wondered what Aunt Margaret meant when she said that a lot of the “intellectuals” had to go into hiding to avoid being rounded up by the Communists and that the Red Guard was indoctrinating children to turn in their parents for cultural “sins.” And we listened closely at the dinner table as my parents discussed the latest letter detailing Aunt Margaret’s efforts to join the mass exodus from the island, fearful of a Communist takeover.

In about 1967, my mother and father tried unsuccessfully to sponsor Margaret so she could emigrate to California. They wrote to our local Congressman, Don Edwards, the Department of State, and anyone else they thought could help. As we understood it, part of the problem was that so many people were trying to leave Hong Kong that the United States set a quota for the number of visas it could grant, which it did by a yearly lottery. We anticipated the lottery deadline every year, but Margaret’s number was never drawn. After several years of unsuccessful attempts, she applied for and was accepted as an immigrant to Canada. She arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia in the early 1970s, where she settled near some of her relatives. My mother was dismayed that Margaret had not made it to the U.S., but she was relieved to know her dear friend had finally managed to leave Hong Kong after all the turmoil there.

My mother and Aunt Margaret finally had their long-awaited reunion in about 1973 or 74, when Margaret flew down from Vancouver to San Francisco International Airport. She stayed with us for a couple of weeks, and she and my mother stayed up late into the night laughing and catching up on life, just as they had when they were young college co-eds. When she returned home, there were just as many tears as there was laughter.

Aunt Margaret and I shared a mutual love of foreign languages, and when I announced that I wanted to learn 17 languages like her, she gently corrected me and said she only spoke only eight. She encouraged me to pursue my language studies and suggested that I should visit Hong Kong one day. Just knowing someone who could speak many languages made it seem more possible to study several myself, and I did just that. By 1977, things had calmed down in Hong Kong, and I went there on a familiarization tour for airline employees. I visited some of Aunt Margaret’s friends on the faculty at the University of Hong Kong and had the time of my life. If not for her, I might never had gone there.

My mother and Aunt Margaret continued writing letters to each other as the years went by, but now they talked on the phone from time to time, too. In the summer of 1987, when my mother learned she had cancer, she wrote to Aunt Margaret to break the news. Margaret’s quick response, below, penned in her elegant hand, comforted my mother beyond words:

July 31, 1987

My dearest Joan,

Thank you ever so much for your letter. I was very very saddened & shocked by the bad news & couldn’t be at ease for a whole day or two. I really don’t know what to say to comfort you. I’m sure you’ll know that I’ll pray hard for you for a miracle from God to grant you minimum pain & eventual recovery. I know you have a lot of courage and have done your very best as a good wife, mother, citizen & friend and, prior to that a good daughter.

I am most grateful to you and yours for your generous love and goodwill to me all these years. My great regret has always been that I have not been able to invite you & your husband to come & visit me here as I live in a one-bed room apartment and for the last 10 years have not enjoyed robust health. I so wish to be able to travel down to visit you now but I have not been able to go anywhere for many years. My brothers & sisters come from Hong Kong, Toronto & Michigan to see me year by year & most of the them stay in a hotel – they can afford it, thank God.

I feel nostalgic for all the good times I did have with you and yours. I do remember your parents only too well. Your father bought us two tickets to see a beautiful Chinese play in Chicago and when I said I wanted to buy a watch he got me a lovely gold one for only $15 which I wore for many, many years. He cooked a lovely dinner at Easter for us. It was a fish with dressing that tasted so much like a favourite Chinese dish of mine. Your mother spoiled me right & left, letting me run around the house in my pyjamas all morning so that I could feel completely at home. She called my pajamas “fire-crackers” because the top was a bright fiery red. She was such a sweet kind lady and so hard-working on her dolls. I didn’t say all this to you when I visited you in San Jose because I’m such a shy person about expressing my emotions, but I can assure you I did miss them.

Do let me know how you get on if you feel like writing and whether there is new medicine or treatment the doctor can give you which helps. How is Gilbert taking it all? Are some of your daughters there to look after you?

I am much older than you – 67 now – and have had lots & lots of pain for many years. But I am still up and going most days of the week. I pray God all the time to let me go to Him before too many more years – in peace.

My fondest love to you, Gilbert, Linda & all the girls.

Ever yours,

Margaret

Eleven years later, in April 1998, my husband and I and our young children drove north to British Columbia on Easter vacation. When we arrived in Vancouver, I phoned Aunt Margaret, eager to see her again.

It was not a good day for her. By now, she would have been about 78 years old. She apologized, saying that she was in poor health, and she asked me to call back two days later, on Wednesday afternoon. Wednesdays, she explained, were the days she received visitors. While this seemed a bit formal and old-fashioned, Margaret was very clear, and it was obvious that she had practiced this routine all her life. When I called two days later, there was no answer, and we left for home the next morning.

She continued to write to my father and me off and on after that, but her letters stopped eventually. We never found out why but guessed it had to do with her frail health.

Margaret Yu never married. I think she had several nieces and nephews who looked after her as she grew older, but in all fairness, they probably did not know all her friends to keep them informed about her progress as she grew older. I wish I knew what became of her, but I will never forget how much she meant to my mother and to all our family. She may not have been an official part of our family tree, but she will always hold a special place in our hearts as our honorable and beloved “Chinese Auntie.”

Copyright © 2012 Linda Huesca Tully

Like this:

Like Loading...

,+Oirzaba,+Veracruz.jpg)

.jpg)