Welner “Bing” Tully – (1922 – 2007)

This week, the 1940census.com Ambassador program has asked its “1940s Ambassadors” to write about technology, science, or transportation during the decade of the Greatest Generation.

And when the 1940 United States Federal Census is released in a mere 18 days, one of the first people I will look up will be my late father-in-law, Welner “Bing” Tully.

|

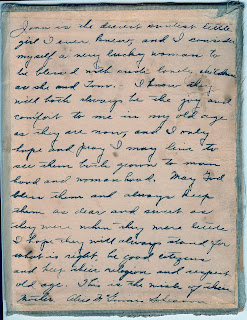

| Amelia Tully, about 1940 |

Bing and his older sister, Vivian, went to live with their paternal aunt, Amelia (nee Tully) Moreno Binning as young children after both of their parents became ill and were no longer able to care for them.

It was middle of the Great Depression. Amelia and her family lived in East Los Angeles. Though the newly extended family lived in a poor section of town, Amelia managed to support her family with the modest earning she made from her small grocery store. She loved Vivian and Bing as if they were her own children, and they were devoted to her in return. Bing helped her at the grocery store after school and tinkered around the house, always trying to fix things for his aunt and make her life easier.

Amelia gave Bing a lot of freedom to explore new things and learn as much as he could, and she would encourage him read and do his homework when things were slow at the store. He stumbled on an advertisement one day for a ham radio kit and became intrigued by the idea of being able to talk to others who shared his passion for science and technology. With no money for luxuries, however, Bing figured out how to build his own radio set, taught himself Morse Code, and obtained a ham radio license to broadcast under the call letters W6RMQ.

|

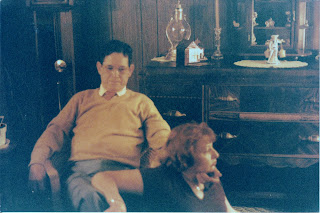

| Wooden sign crafted by Welner “Bing” Tully |

The romance of communications and its many media appealed to Bing, a gregarious and affable young man who was fascinated by the boom of technology. In 1940, at age 18, he took a job as a messenger delivering telegrams for Western Union, often riding his bicycle across long stretches of Los Angeles to deliver good news and bad to all kinds of people. Though he never opened the envelopes, he wondered what kind of reaction they would elicit from the receivers – joy or jubilation, shock, or sadness.

Bing Tully’s career as a messenger boy was short-lived when a jealous man had him fired for what he misconstrued as advances on his girlfriend. He thought the woman had asked Bing to wait while she left the room to get a pen to write down her phone number. It turned out that she was getting her purse to give him a tip. Unfortunately for Bing, it would be his last one as a Western Union man.

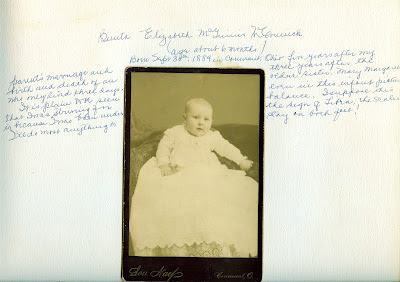

+Tully,+about+19+yrs+old,+Los+Angeles,+ca.+1941.jpg) |

Welner “Bing” Tully, 19 years old

Los Angeles, Calfornia, 1941 |

Sunday, December 7, 1941, marked a turning point in his young life when, like most Americans, he learned from a radio broadcast of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Though families had gathered around their radio sets to hear the news and enjoy live music, comedy, and serial programs together for years, they did so purposefully and urgently now, listening to constant updates on the tragedy and on the ensuing American involvement in what was now World War II. “Stay tuned,” was a familiar refrain that began during radio days and made its way into the culture of the time as a way of letting you know that something important was coming.

And something important came, indeed. Radio took on new importance for Bing and many young men of his generation as it became a powerful – and potentially dangerous – wartime tool. In 1940, the United States federal government had passed the Telecommunications Convention, prohibiting the 51,000 American amateur radio operators from communicating with other hams outside the U.S. and requiring all licensees to send their photo, proof of U.S. citizenship, and a set of fingerprints to Washington, D.C.

Once the U.S. entered the war in 1941, the government suspended ham radio operations completely in the interest of national security. Full operation would not be restored until 1946.

Skilled amateur radio operators now became valuable resources for the U.S. military, and over the course of the war, about half of them – some 25,000 in all – signed up to serve their country.

Bing was one of these volunteers, entering the Army Air Corps at Hammer Field in Fresno, California, on February 4, 1943, as a Private First Class, Service Number V19100848. Originally hoping to become a pilot, he was rejected some five months into his training when his instructor learned he had fainted once as a child during a Southern California heat wave.

The Army Air Corps reclassified him as a radio operator and assigned him to the 4th Combat Cargo Group in the China-Burma-India theater. He and his fellow soldiers arrived in Sylhet, India, just after Thanksgiving 1944, where they joined a task force of Canadians and Australians, providing airpower support to the British 14th Army, which was retaking Burma from the Japanese.

CCG aircraft transported reinforcements and supplies for the Allies, moving supplies for the construction of the Ledo Road, carrying men, mules, and boats across the Irawaddy River, and flying soldiers, gasoline, and ammunition over the Burma “hump” to China.

In May 1945, just a few days after the war had officially ended, Bing and 7 other men were sent to repair some runway lights at Meiktila, a beleaguered airstrip and constant source of fighting between the Allies and the Japanese. The lights always needed repair or replacing, because the Burmese liked to take the colored glass and melt it down to make it look like valuable stones or gems. For some reason, before the men could finish repairing the runway lights, their pilot took off without them, leaving them stranded there for three days.

The war may have been officially over, but the area surrounding the field remained treacherous, with pockets of enemy troops here and there. Bing tried radioing in code for help, using fake call letters, so as not to alert any remaining Japanese who might pick up his signal. When his calls went unheeded, he decided to take a chance and used another American’s radio transmitter to radio to Chittagong in English: “Tully here.”

“Hannan here,” came back the reply. Bing recognized the name as that of his bunkmate. He could finally relax. “8 men with runway lights stranded at Meiktila. Require transportation back.”

A C-46 arrived shortly, and the men continued on their duty. It would be some nine months before Bing left for Calcutta and departed on the troop ship Marine Wolf for San Pedro, California, stopping briefly in Honolulu, Hawaii.

The 4th CCG was inactivated on February 9, 1946. Bing Tully was discharged as a Staff Sergeant a day later in San Pedro, after three years of service. He would always remember his days with the 4th CCG with fondness.

I always thought I knew my father-in-law well, but like many of his “great generation,” he downplayed his role in the war. He downplayed his life, too, preferring modesty to boasting about himself or his adventures and good deeds. Perhaps I’ll find out more about him soon in the 1940 Census, which by the way, is looking for volunteer indexers in its 1940 Census Project. Why don’t you join me? It should be a lot of fun.

Stay tuned.

Copyright © 2012 Linda Huesca Tully

Did you know Welner “Bing” and Vivian Tully or their aunt Amelia (Tully) Moreno Binning; or are you a member of the Hoppin, Tully, Moyer, or Moreno, or Binning families? Were you or was someone you know assigned to the 4th Air Combat Cargo Group in the CBI Theater? If so, share your memories and comments below.

Like this:

Like Loading...

+Tully,+about+19+yrs+old,+Los+Angeles,+ca.+1941.jpg)