Introduction: In the spring of 1978, my father, Gilbert Huesca, sent my mother, Joan Huesca, then 49, on a flight to Mexico City to visit his family while he stayed behind in California to tend to business matters. During this visit, she and three of our relatives were caught in one of the deadliest fires in Mexico City’s history, known as the Astor Fire. My mother wrote a letter to thank her rescuers shortly after returning home to California. She recounted this nightmarish tale many times to my father, my sisters, and me in the years that followed, always emphasizing that life and the people in it are gifts to be treasured. This is Part Six in a seven-part series about that night, based on my mother’s recollections, those of my relatives, and my research on the event. – L.H.T.

.JPG) |

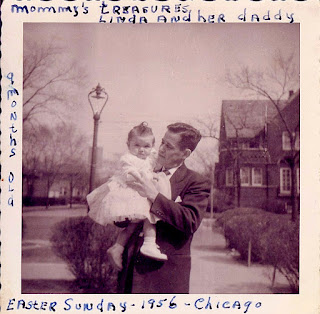

| Mexican firefighters survey the ruins of the seven-story Astor Department Store after it collapsed during a fire, fatally burying several firemen and injuring others. |

My father left our family’s home in California to catch a flight down to Mexico City right after my mother called him on Saturday morning about the Astor fire.

That same afternoon, my cousin Eduardo Huesca returned downtown to his family’s home in the La Galia Building on Venustiano Carranza Street to see for himself the final outcome of the fire. “I needed to find out if it was okay. This was my father’s legacy – his home, his business.”

He arrived there at about 1:00 p.m. By then, firefighters had successfully extinguished the fire in the La Galia, where only hours earlier they had rescued the Huescas and another family. They also had been able to get the blazes under control at both the Astor and Blanco department stores, a block apart from each other.

Eduardo headed through the mezzanine of the La Galia, past a service corridor that connected the building with Astor. The fire, which had originated at Astor, had spread through the passageway into the La Galia.

Now the passageway was wide open, its steel curtains having been forced apart by the firefighters at some point. As he paused briefly, he spotted the charred remains of someone inside. (1) The body may have been of the store’s night watchman, who was said to have burned to death in the fire. (2)

Eduardo hurried upstairs, stopping at the fifth floor to survey his father’s linen embroidery business, Sábanas y Manteles (Sheets and Tablecloths).

“Everything was damaged,” he recalled. “Later on we were able to remove some things and wash some of the fabrics that survived in better shape. They were all we had left, and we had to use them.” His older brother, Enrique Jr., who also returned to the building two days after the fire to spare his father the anguish of seeing the damage, would remember that even then hot water was still dripping from the ceilings through to every floor. (3)

The penthouse, though smoke-damaged, did not fare as badly as the business. The family ultimately was able to salvage most of their belongings, except for their electronics and appliances, which later were stolen by looters.

At about ten minutes after three on Saturday afternoon, not long after Eduardo left the La Galia Building, the Astor Department Store collapsed. It brought down in its wake a telescopic ladder and buried a number of firefighters under its smoldering ruins.

.JPG) |

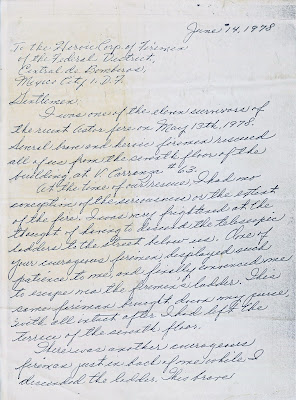

| A surreal photo shows members of the Heroic Corps of Firefighters digging through the debris of the Astor Department Store to find the bodies of their comrades. |

An article by Pablo Viadas in a construction magazine, Construcción y Tecnología, pointed to the building’s steel structure as a factor in the collapse. Viadas surmised that the fire created an oven in the early twentieth century building, the high temperatures softening the steel so much that it gave way under the weight of the structure. (4)

Indeed, the toll of the two fires that night was high. The Astor and Blanco fire would go down in infamy as one of the worst fires in Mexico City’s history.

More than 500 firefighters were called in that night to fight the inferno. Conflicting newspaper articles reported that of those, some 7 to 10 lost their lives. Over 50 people were injured, and a total of 15 families, including my mother, my uncle Enrique, aunt Meche, and cousin Eduardo Huesca, were rescued from neighboring buildings.

The Heroic Corps of Firefighters official website lists the following names of seven firefighters who died in 1978. Though the site does not mention their month and date of death, it would appear that they died in the Astor fire:

First Sargent Roberto Ríos Miranda

Fireman Alfonso Torres Martínez

Fireman Rodrigo Quezada Molina

Fireman Juan Jorge Aceves Cortina

Fireman César Valverde Cueto

Fireman Lázaro Márquez Guzmán

Lieutenant Adalberto González

True to the name of their department, these firemen served their city heroically and faced the daunting challenges of the fire of May 13, 1978, calmly and bravely. When Astor fell and took them with it, these men made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives so that others could live. Their families, too, made untold tremendous sacrifices that night when they lost fathers, sons, husbands, and brothers. Though many of us wish there were a way we could thank them today for the gift they gave our own loved ones those 35 years ago, we will always honor them and hold them dear in our hearts.

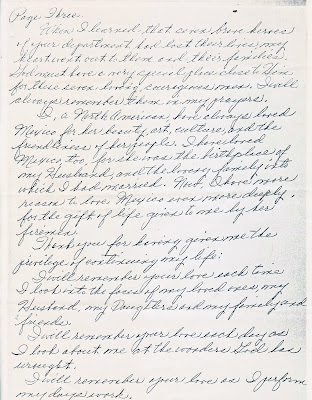

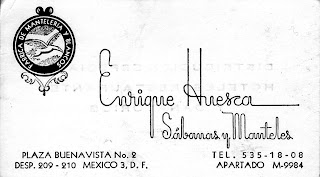

My cousin Enrique eventually found a new apartment for his parents. He also helped them find a new location for the business at #2 Plaza Buenavista, where the family relocated whatever they could recover from their offices in the La Galia Building.

|

Enrique Huesca’s business card with his new address

after the Astor fire. |

Not long after the fire, Enrique Sr. and his sons visited some of their suppliers. “We asked them to help us,” Eduardo remembered, “but with no luck. After being turned down several times, we visited a Jewish businessman. ‘Huesca,’ he said, ‘just go and buy whatever you need for the business and don’t worry about the money. I believe in you. I know you’ll come through.’

“He gave us a second chance and saved my father’s business,” Eduardo said. “I don’t know whatever happened to that man, but even to this day, every night when I go to bed, I pray for him and his family.” Sábanas y Manteles went on to operate successfully for another two decades, until my uncle Enrique retired in 1995. (5)

In 1982, the Mexican President, José López Portillo, ordered that a park be built on the property in honor of the recent bank nationalization. The park lasted a few years until a new building took its place.

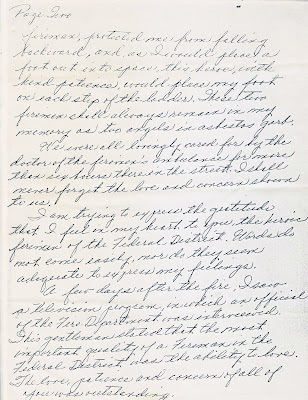

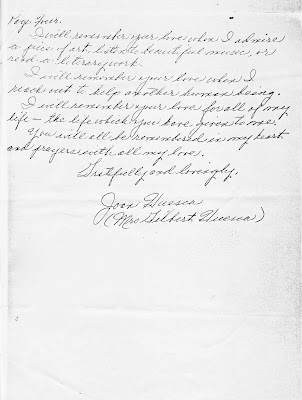

My parents flew home to California just days after the Astor fire. About a month later, my mother wrote a letter to thank the Mexico City Fire Department for saving her life.* She and my father would return to Mexico several times after that. Both the love they shared for that country and the bond between them and our family were now stronger than ever before.

(1) Huesca, Eduardo. Telephone interview. April 7, 2013.

(2) “At least 4 dead as stores burn in Mexico City,” Associated Press, Eugene Register-Guard, May 14, 1978. Web. Accessed March 25, 2013.

(3) Huesca, Enrique. Telephone interview. April 6, 2013.

(4) “The Thermodynamics of Fire.” Construcción y Tecnología. Mexico City, D.F., U. Medellín: Mexican Institute of Cement and Concrete, IMCYC,. 2002, No. 166, pp. 36 – 38. Web. Accessed April 3, 2013.

(5) Huesca, Enrique.

* A transcript of my mother’s letter will be published in Part 7 , as the conclusion of this series.

NEXT: Part 7 – Epilogue: I Will Remember

To read the other installments in this series, please click on the links below:

The Astor Fire, Part 1 – The Gift of Life

The Astor Fire, Part 2 – Explosions

The Astor Fire, Part 3 – In God’s Hands

The Astor Fire, Part 4 – Angels in Asbestos Garb

The Astor Fire, Part 5 – A Firefighter’s Ability to Love

The Astor Fire, Part 7 – Epilogue: I Will Remember

**********

Copyright © 2013 Linda Huesca Tully