María Angela Catalina (Perrotin) Huesca

Born May 31, 1893, in Orizaba, Veracruz, Mexico

Died April 5, 1998, in Mexico City, D. F., Mexico

My grandmother, Maria Angela Catalina Perrotin, was the third child born to Francisco Perrotin and Maria Amaro. Her birth certificate notes that her father, age 26, was from Orizaba and was a mechanic, presumably for Ferrocarriles Mexicanos, the Mexican Railway. Her mother, Maria, age 20, hailed from Tecamachalco, in Puebla, Mexico.

Catalina was one of six brothers and sisters. She is in the top picture, dated September 28, 1893, with her parents and brother Francisco. I would guess the family is outside their home, and their dress suggests that it may have been the occasion of the infant Catalina’s baptism.

Catalina, her brothers Francisco, Hugo, Roberto and Juan, and their sister, Blanca Luz, grew up speaking English and French in addition to their native Spanish. They often used their multilingual abilities to share secrets with one another, sometimes going back and forth between English and French when they wanted no one outside the family to hear their conversations. This was particularly handy when Catalina became a parent, as she could easily share confidences with her sister and mother without her children understanding them!

Years later, however, when my family moved to Mexico City, my grandmother had forgotten how to speak English, but she still understood every word we said, sometimes even when we mischievous little girls thought she didn’t — much to our chagrin and the delight of our parents.

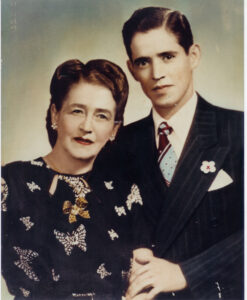

In 1899, when Catalina was only six years old, her father, Francisco Perrotin, died of Yellow Fever. The epidemic, known then as el vomito negro (the “Black Vomit”) in Mexico, claimed over 600 lives in Veracruz state that year. To make ends meet, her mother, Maria, ran an eatery in Orizaba, and it was while helping her mother there that the young Catalina met the love of her life, Jose Gil Alberto Cayetano Huesca (known to all simply as Cayetano Huesca). The couple married sacramentally in 1908 (and civilly in 1912); Catalina was barely 14 and Cayetano was 18. Though today we might flinch at the thought of such a young bride, it was not uncommon at the time, and it is possible that Catalina saw marriage as a way of easing the financial burden on her mother.

Catalina gave birth to her first son, Enrique, in early 1909. She and Cayetano would have 16 more children, though six of them never made it past toddlerhood. Half of the children had their father’s dark hair, while the other half were either blond or red-headed, with blue eyes reflecting their mother’s French-Irish background.

Feeding, housing, and clothing a large family was challenging in those days. In addition to Cayetano’s work as a mechanic for Ferrocarriles Mexicanos and his efforts to improve labor conditions for railroad workers, he and Catalina bought and operated a hotel, casino, and skating rink in Tierra Blanca, Veracruz. Each of the children helped in the business. My father’s job was to make the beds every morning before he went to school. The others did the dishes and the laundry, swept and mopped floors, and transported guests’ baggage from the Tierra Blanca train station to the hotel.

Cayetano Huesca died of pneumonia in 1937. Catalina, at 44 years old, had given birth about eight months earlier to her youngest child, Edilberto, and she still had a large family to support, though some of the older children were already grown and had left home. Still, she inherited the strength inherent in the women of her family and moved forward, never complaining but taking the challenge in stride. She took great pride in her children, who adored her and continued to honor her for the rest of her life.

On the heels of Cayetano’s death, the Huesca family moved to Mexico City, as did Catalina’s mother, Maria (Amaro) Perrotin, and sister, Blanca Luz Perrotin. As her children grew and began their own families, she stayed involved. She held court on Sundays, birthdays, and holidays in her little house on Carpio Street in Colonia Santa María la Ribera, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Mexico City, where her children and over 100 grandchildren and great-grandchildren would come to visit. She knew everyone’s name and age and never forgot a birthday, and she made each person who visited her feel as though he or she were her favorite.

Her typical morning routine consisted of sweeping her tile floors with a broom of long pieces of straw wrapped tightly around a stick. First thing in the morning, she would throw open the metal doors to her inside patio and put out the cages with her beloved yellow and orange canaries, where they would sing the sweetest songs and soak in the sunshine as she went about her work, tending to the multitude of potted tropical plants and flowers in the patio, washing floors, doing laundry, and cooking. Every morning she went to the market and bought the day’s groceries. Her mother, Maria (Amaro) Perrotin, and sister Blanca Perrotin, often joined her around two o’clock in the afternoon for the customary Mexican comida, or dinner.

It was the day’s big meal, and businesses and schools would typically close at 1:00 or so in the afternoon so employees and students alike could go home and eat with their families. People would then return to work from 5 to 9 p.m., after which they would come home for a nightcap, or cena, which consisted of Mexican sweet rolls, or pan dulce, which all families bought nightly at the corner bakery.

The comida at Catalina’s house usually consisted of several elaborately made courses: appetizers, sopa de fideos (chicken noodle soup), rice, frijoles (beans), chiles rellenos (stuffed green peppers), tacos or enchiladas or beef steak, coffee, and often slices of fresh mango or papaya for dessert. Catalina was an excellent cook, and in her tiny kitchen, she could cook just as easily for one as she could for 50. She did this often for the steady stream of children and grandchildren who visited her to chat or celebrate birthdays, holidays, and special occasions.

My Abuelita (an endearing term for “Grandmother” in Spanish) Catalina was a devout Roman Catholic and was strongly devoted to St. Martin de Porres. She kept a worn framed picture of him on the back of her pale green front door, along with a prayer beneath it and a small shelf on the wall next to it that held votive candles and pictures of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and Our Lady of Guadalupe. She displayed the same pictures in her bedroom, and every night before bed, she slowly walked around the room, lighting votive candles under these images and pictures of my Abuelito Cayetano and every member of their family, living or dead, as she prayed for each person. With our large family, this usually took her between 30 – 45 minutes every night.

My precious Abuelita loved her family deeply and had an incredible recollection of names, dates, and even voices. Even after she turned 100 years old, she recognized my voice whenever I called her on the telephone from over 2000 miles away in California. She always asked right away about my husband, our children, my sisters, and of course, my father. Though my mother had died some years earlier, my grandmother never let a phone call go by without recalling her affection for her. I could have gone on listening to her voice all night.

Like the women who came before her, she was strong, active, and independent all her life. In her late 90s, she moved from her home on Carpio Street to an apartment a few miles away in the Narvarte neighborhood, next door to one of her daughters, where she continued to live alone until her death at age 105. Her spirituality, independence, strong work ethic, and fierce devotion to family live on in her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, each of whom was special to her and who adored her in return.

I dream about her often, and she will always live on in my heart.

Copyright © 2012 Linda Huesca Tully

Hola Yo soy Alma Lidia Rodríguez Anaya, hija de Martha Anaya Huesca, hija de Luz María Huesca Perrotin, hija de mi bisabuelita Catita, es un gusto y un placer poder leer todas estas historias , de las cuales tengo en mente varias de las que mi Madre me ha contado, un gusto poder saber de tu existencia y poder tener contacto, que por lo que veo soy una de tus sobrinas 😃

Querida sobrina Alma,

Qué gusto fue recibir tu mensaje! Es un placer conocerte. Te agradezco haber tomado el tiempo para comunicar conmigo, y voy a responderte directamente por e-mail.

Mientras tanto, recibe un fuerte abrazo para tí, tu familia, y mi prima Martha.

Linda