Ralph Schiavon

Young Immigrant in a New World

|

| Ralph Schiavon, Boston, about 1910 |

(Second in a four-part series)

Like most newly-arrived ethnic groups during the turn of the century, Italian immigrants dreamed of becoming successful in America. This meant owning their own home. To the former peasants who for decades had endured la miseria – a miserable existence of innumerable indignities and hopelessness and poverty in their native land – home ownership, the ultimate definition of prosperity to the Southern Italians, represented independence, security, prosperity, and self-respect.

Vito Schiavone, who first arrived in America in 1890, had lived for a time with his brothers-in-law in a tenement house at 198 Endicott Street at the heart of Boston’s North End. Living in that crowded, dirty neighborhood had made him determined to buy his own home in another part of town so his family would not have to bear such oppressive conditions.

The dream was not unachievable, but it depended on great sacrifice and effort on the part of everyone in the family. Vito pulled Ralph out of school as soon as he was old enough to work and sent him to join his brother Pat in a shoe factory in Roxbury. Child labor was commonplace at that time, and boys and girls in the shoe factories made up about seven percent of the total workforce in the Boston boot and shoe industry.

Children were given jobs that required little training, such as stitching shoe uppers or working in the shipping department. Ralph worked in shipping, putting in 10 hours a day Monday through Friday and half a day on Saturdays, rain or shine.

Shoe leather would arrive at the factory in wooden boxes. Once the crates were emptied, Ralph would break them down flat and load the wood into a small wagon so he could sell it. For this he was paid about $6.43 a week, the average wage for a child laborer of the time. (Men and women, by comparison, earned on average $15.17 and $10.39 a week, respectively.)

The long dreary hours left the boy without much time for a childhood. He never had a toy of his own and had little time for play. Instead, money took on great importance in his young life as he worked long hours to help support his family. Like other young boys, he learned to save at an early age and often walked the long distance home rather than take the streetcar, so he could have more money to give to his parents.

One freezing winter day on his way home, young Ralph met a man who gave him some baby chicks that were nearly dead from the cold. He tucked them into his wool coat to keep them warm and set aside some of the wood from the shipping crates to make coops for them.

Upon entering the kitchen, he removed his coat and proudly showed his new pets to his parents. While Emanuela cooed at the chicks, Vito flew into a rage at the thought that Ralph had lost money by bringing home the wood instead of selling it. He rose from his chair and thrust his fist at his son. Emanuela jumped in between them to block her husband. Vito’s fist, meant for Ralph, struck Emanuela instead, knocking out her front teeth.

Emanuela recovered and nursed the chicks with an eyedropper and a little wine and warmed them on the oven door. Ralph never forgot his mother’s loving sacrifice for him. Needless to say, the chicks may have been pets for a time but ran the usual course that chicks do and eventually made their inevitable appearance on the dinner table.

|

| Postcard of Wonderland Amusement Park, Revere, MA |

|

| Nicholas Schiavone, Boston, 1910 |

Tragedy struck the family in the spring of 1911 when eight-year-old Nicky Schiavone drowned in the marsh behind Wonderland Amusement Park, a popular Revere landmark in the early 1900s. He and Ralph had been playing in the marsh with a young neighbor, Leo Dowling, when Leo began flailing his arms. Nicky managed to rescue Leo but got caught in the marsh himself and began sinking into the muck. Ralph watched in horror as the thick mud sucked his brother in deeper and deeper, until he drowned.

Some would later say that Ralph’s “lucky veil,” or caul, had protected him from the same fate as Nicky, but it seems that Ralph was in fact burdened by the fact that he had been spared instead of his brother. The accident haunted him for the rest of his life, and he never forgave himself for not being able to save his little brother. His children (my mother Joan and my Uncle Tom Schiavon), as well as my own sisters and I, heard the story over and over as we grew up, along with a coda of instructions on how to save a drowning person.

When Filomena married Tomasso Scicchitani in 1913 and Pasquale (known as “Pat”) married Dora Salemme two years later, Ralph became the oldest child of those still living at home. He took on the role of a third parent to Tony and Leo, sometimes treating them more strictly than their own parents, much to the chagrin of the younger Schiavones. Perhaps he was overcompensating for his inability to save Nicky. From what I have heard from my own mother, Joan Schiavon, and my cousins, he saw it it that his youngest brothers would not have to leave school as he did at a young age to work. Even in his youth he comprehended the value of an education as a path to success, and he encouraged Tony and Leo to continue their studies, making it very clear that he expected them to graduate at the top of their class.

|

Ralph entered the United States Navy on August 26, 1918, and received his training in Norfolk, Virginia.

Assigned as a Seaman Second Class on the submarine USS Carolina. The tight quarters of submarine made him feel claustrophobic, and he was relieved when he was later transferred to the battleship USS Kansas. He was a member of a crew that traveled to Brest, France, at the end of World War I to bring many of the Special Expeditionary Forces home to America. His jobs entailed standing various forms of watch, such as lookout and security, and his days would have consisted of learning such basic duties as being part of the gun crew; setting up and using rigs for loading fuel, ammunition, and supplies; firefighting; food cleanup; sweeping and swabbing decks; and painting and polishing equipment.

Two months after he enlisted, the Armistice Treaty was signed on November 11, 1918.

In 1919, Ralph was stationed at Great Lakes Naval Station, near Chicago, Illinois. One day while on leave he met Benita McGinnis, a young artist and member of the Chicago Movie Censorship Board. After dating her briefly, he was invited to her home, where he noticed her younger sister, a lively, 26-year-old redhead named Alice. He was smitten immediately by her laughter and sense of adventure and soon began courting her instead of Benita.

Although we do not know for certain how it happened, it seems that the McGinnises did not know Ralph was Italian when they first met him. He may have deliberately dropped the “e” at the end of Schiavone, which would have put the accent on the last syllable and made it sound French, or maybe it happened some other way. (In later years he would say that the U.S. Navy had dropped the “e” from his name to make it sound more American. His service record and his naturalization petition, however, do not show this to be so.) He apparently was afraid of being found out as Italian and said nothing to change Alice’s impression that she was in love with a Frenchman.

|

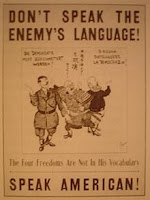

| Speaking the language of the Axis powers during World War II was considered “Un-American,” as shown in this poster. |

His fear was not unfounded. For years, Italians, in particular those from the south, had been perceived as gangsters, womanizers, and lower class members of society. They had been subjected to ethnic jokes and racial slurs such as “goombah,” “wop,” and “dago.” During both World Wars, Italians were viewed with suspicion and often regarded as Fascists. Italy being an enemy nation during World War II, the six thousand Italian aliens then living in the United States were required by law to register as “enemy aliens.” This included Ralph’s mother, Emanuela, who had never changed her citizenship. In a lesser-known incident, several hundred Italian-Americans on the West Coast were rounded up and interned in detention camps from 1941-1943, not because of anything they had done but simply because they were Italian.

In later years, Ralph himself would be mistaken for Benito Mussolini, the Italian dictator, as well as for the infamous mobster Al Capone. In the latter case of mistaken identity, the Chicago police actually stopped him for a short time, releasing him only after verifying his identification.

Considering that Italians were at the bottom of the ethnic ladder in those days, it must have been a difficult decision for Ralph to change his last name to something that sounded less Italian. Some of his family were hurt by this action and believed that he had been disloyal to his heritage. They may have had valid reasons to feel that way, as they, too, had faced the same prejudice and discrimination – perhaps even more so because they kept their family name.

But the truth is that Ralph was not alone. Many of his countrymen changed their names to avoid bigotry and discrimination, sometimes even translating their surnames into English. Ralph was proud to be Italian and would never dishonored his origins, but he, as any other human being, had a right to be treated with dignity and respect. Though we may never know the depth of the inner struggle he must have experienced over this decision, we can be certain that ultimately he did what he felt he had to do in the climate of the time.

Ralph was granted U.S. citizenship on May 12, 1919, two weeks before he was discharged from the service at Great Lakes Naval Station. He returned to his parent’s home on Eastern Avenue in Revere and began a long-distance correspondence with Alice that would span nearly four years.

|

| Ralph Schiavon, second window from rear, Cologne, Germany, early 1920s |

He found a job selling shoes at a store in Revere. He soon discovered that he enjoyed working with numbers and solving problems more than selling shoes, and he began taking night school classes in accounting. He also seems to have returned to Europe after World War I, as the photo above shows.

Alice McGinnis accepted his proposal sometime in early 1923, setting off a short personal crisis for Ralph as he realized that “the jig was up.” He knew it was time to honest about his nationality, even if it meant losing the woman he loved.

He wrote Alice a passionate letter that spring. In it, he confessed his Italian nationality and apologized for having deceived her, explaining that he had not wanted to lose her. He went on to tell Alice how much he loved her and that he dreamed of opening a small general store in Chicago so he could always take care of her and she would never have to work. He closed by adding that he would understand if she decided to break off the engagement.

Alice McGinnis was not one to reject someone on the basis of his origins. She understood prejudice only too well, as she and her family had experienced it first-hand as Irish-Americans. It had not been that long ago that her grandfather, father, and brothers had been excluded from jobs whose ads warned that “Irish need not apply.”

She wrote back to Ralph right away and forgave him. The couple were married on June 18, 1923, at Saint Joachim’s Church in Chicago and honeymooned at Starved Rock Park, a popular campground not far from Chicago.

Copyright (C) 2011 Linda Huesca Tully

Next: Part Three – Halcyon Days