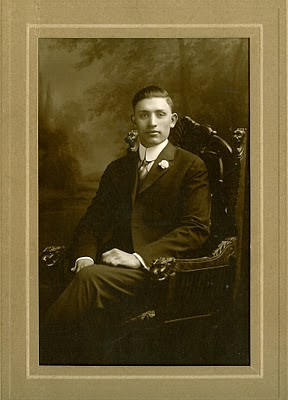

Ralph Schiavon

Born January 27, 1898

Died August 16, 1970

The following is Part One of a four-part series on the life of my wonderful Italian grandfather.

Auspicious Beginnings

My maternal grandfather, Ralph Schiavon, was one of those rare children born with a veil over his head.

The “veil,” known medically as a “caul,” was part of the amniotic membrane that covers a child’s face or head. This occurs in about 1 out of every 80,000 births. Italian superstition viewed this as an omen that such children were destined to be special and do great things, as they had gifts of wisdom and vision (also called “second sight”). The caul was seen as a lucky talisman that could protect a person from harm, especially from drowning. For this reason, it became popular for many seamen to seek these out and purchase them for personal protection. However, others viewed the caul as a curse because it supposedly brought great challenges and heavy burdens.

As was tradition for such a special circumstance, Rosina Coppola*, the midwife who delivered Ralph, rubbed a sheet of paper across his head and face so that the material of the caul would stick to the paper. She then presented this new treasure to the child’s happy mother, who sealed it in a small jar for safekeeping. She later carried it across the sea on the ship to America, eventually giving it to her son when he grew old enough to take care of it. My mother said that Ralph kept the caul with him all his life.

Ralph was the third of six children born to Vito Schiavone and his wife, Emanuela Sannella, on January 27, 1898, in San Sossio Baronia, Avellino Province, just east of Naples, Italy. Most of San Sossio’s residents were poor and illiterate and were leaving the village in droves, and many families emigrated to Boston and its environs. Vito Schiavone left for America in 1890, barely three years after Emanuela gave birth to the couple’s first child, Pasquale. He returned at intervals to San Sossio as daughter Filomena and sons Ralph and Nicholas were born.

Ralph, named for his mother’s father, Raffaele Sannella, was born with a “caul,” part of the placental membrane covering his head. Italian superstition had it that such children were destined to be special and do great things, as they had gifts of vision and wisdom. The caul also was said to protect a person from harm and especially from drowning. For this reason, it became popular for many seamen to seek these out and purchase them for their own protection. However, others viewed it as a curse because it supposedly brought with it great challenges and heavy burdens. Emanuela’s midwife placed the caul, also called a “white veil,” into a small jar for safekeeping and gave it to the happy mother, who later passed it on to her son. My mother said that Ralph kept it with him all his life.

Emanuela sent Ralph to live with some maiden ladies – possibly relatives? – for the first years of his life. She may have needed help because her husband was away in America for much of that time. The ladies were a bit better off and kept him well-fed and healthy. They owned several farm animals, one of them a goat, from which Ralph would drink milk directly and then ride around until he was too big to carry.

San Sossio had a rivalry with San Nicola Baronia, a village on a neighboring mountaintop. One night before Christmas, as the Sossians prepared for their annual saints’ procession through the village, some of the rival townspeople sneaked into the village and stole the statues for their own procession. A rock-throwing war between the villages ensued until the culprits returned the statues.

In her 1987 autobiography, my mother wrote of one of Ralph’s earliest adventures:

When Daddy was five or six, he and some of his friends met on the Church steps in the village square and planned to undertake a hunting adventure. One boy would bring a gun, another the ammunition, another some spaghetti, and still another, some tomatoes for sauce, and they would go out into the woods to catch their dinner. Off they went, but to their dismay, all they could catch were some little birds. They decided to make the best of their spoils. Cook dinner they did, and when it came time to add the “meat,” they threw in the birds – complete – feathers and all! Needless to say, dinner was not a success!

In 1902, Vito declared that 15-year-old Pasquale was ready to go to America, and he took him along to New York on the ship S.S. Washington that May. By then, he had rented a house on Tapley Avenue in Revere, determined that the family would not live in the Boston tenements that housed so many other Italian arrivals. Even so, Revere was a working-class town, and rents were relatively expensive. So, like many of his fellow villagers and cousins, son Pasquale (known as “Pat” in America) went to work at a shoe factory in the Boston area. Father and son saved their earnings carefully until they could send for the rest of the family.

It took four years, but finally, in 1906, Vito sent Emanuela the money she needed to buy passage in the steerage compartment for herself and children Maria Filomena, 16, Ralph, 8, and Nicholas, 4. The little group departed Naples on October 6, 1906, on the S.S. Republic. The trip took 48 days, with the Republic arriving in Boston Harbor just before Thanksgiving on November 23rd.

Times were hard, and like many newly arrived immigrant families, the Schiavones expected those children who were old enough to work to help bring in enough money to house, feed, and clothe their growing family, especially as Anthony and Leo were born in Revere in 1908 and 1910, respectively. Vito and Emanuela were frugal and in a few years, managed to save enough money to buy a house just around the corner at 33 Eastern Avenue. It was near Saint Anthony of Padua Church, where Ralph would serve as an altar boy for many years.

|

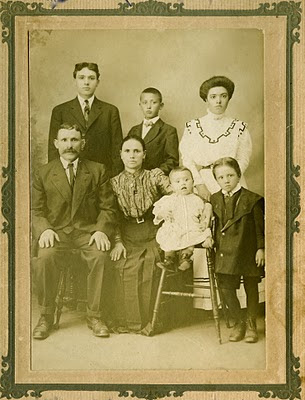

| The Schiavone Family, about 1910 Left to right, back row: Pasquale, Ralph, and Filomena Front row: Vito, Emanuela, Anthony, and Nicky Photo by Fotografia Italiana, Hanover Street, Boston |

Not long after arriving in America, Ralph began selling newspapers after school. He also worked for a time helping load pianos on freight cars. Though his jobs left him little time for homework, he was a natural student and a quick study. His principal at the Shurtleff School, Miss Adams, called him “brilliant” and “very businesslike.” Perhaps the latter description was more revealing than at first glance, as it is clear that Ralph had to grow up quickly. Unfortunately, Vito, who, like many of his fellow immigrants, had never learned to read or write in the old country, decided in 1908 that Ralph had spent enough time at school and should be working full-time to help support the family. Over Miss Adams’ loud protests, he pulled his young son out of the third grade and sent him to work in Roxbury at the same leather shoe factory as his brother Pat. Ralph, who loved school, was devastated, but he had no other choice but to obey his father. He was barely 10 years old, but the greatness for which he had seemed destined at birth was waning in his eyes.

* Rosina Coppola reported Ralph’s birth at the Town Hall in place of his father, Vito, who was in America at that time.

Copyright (C) 2011 Linda Huesca Tully