History classes bored me when I was young. They seemed too focused on battles, dates, and dry facts and names that meant nothing to me. Aside from those who interested me, such as Galileo Galilei, Henry XIII, Marie Curie, Abraham Lincoln, and Charles Lindbergh, most of the people in my history books had no seeming relevance to my life.

Stories were more up my alley: fairy tales and myths, fiction and non-fiction, biographies, and family stories. Reading about people, their experiences, and their feelings was my escape from the world. Listening to family stories around the dinner table brought me back into it, wide-eyed and rapt in wonder at the marvelous things my grandparents, great-grandparents, and aunts and uncles had seen, done, and thought, at times practically in my own backyard. The idea that these people made me who I am has spurred a curiosity to learn as much as I could about them, and so began my lifelong love of genealogy.

History becomes more relevant and interesting when you have a personal connection. As we try to make sense of the world of our forebears, we begin to understand that their stories and the historical events and people behind them are also part of our own story. As American historian Doris Kearns Goodwin has written, “The past is not simply the past, but a prism through which the subject filters his own changing self-image.”

With a growing curiosity to uncover more about my family and their stories, I paid closer attention to the surroundings and events that affected their lives. My youthful boredom with history transformed into a fascination with it and its relevance to my life and those before me as I began to look in new ways at my ancestors’ lives and motivations in the contexts of their time and place in the world.

Although as a California resident I knew a fair amount about the Gold Rush of 1849, it took on personal meaning through the family stories of my great-great grandfather, William Constantine McGinnis, who found gold, fell ill, and had to be nursed to health by his wife, Margaret McCoy, who sailed from New York to San Francisco around Cape Horn to be by his side.

I learned of the immigrant’s perspective on the same period from my husband’s own great-great grandfather, Joseph Edouard Baron, who left his family in the south of France during an economic depression to seek his fortune in California.

When we moved to Gilroy, about 30 miles south of San Jose, I set my sights on visiting the local historical society and museum. It was there I ran across mentions of two men named Tully, my husband’s surname. One was an ancestor, the other possibly his cousin. Both were early settlers. Researching their places in the history of Gilroy gave me added appreciation for my newly adopted hometown and surrounding area.

Our children didn’t have much of a chance to dislike history. I took every opportunity I could to connect them with historical events. They knew the stories about their Hoppin pilgrim ancestors; their ancestor Zachariah Riney, who taught Abraham Lincoln to read and write; and their Grandpa Welner “Bing” Tully being stranded in an airfield in Burma during World War II. History came alive for them and helped them gain a wider perspective of the world and how they fit into it.

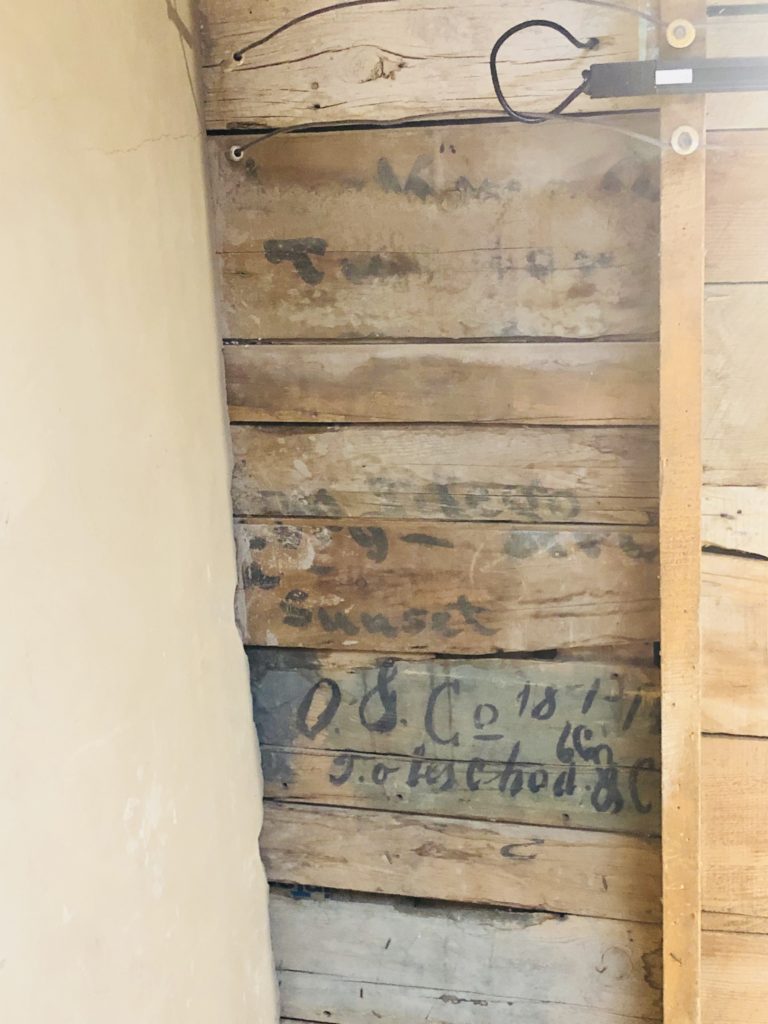

Last March, on a family history sleuthing trip to Tucson, Arizona, my husband, our son Kevin, and I snapped pictures of each other in front of Tully Elementary School, named for my husband’s second and third great-grandfathers, Charles Hoppin Tully and Pinckney R. Tully; and gazed up at the ceiling of the old Presidio, made up in part from freight boxes from Tully & Ochoa, their mercantile company.

Charles H. Tully, an educator and journalist in early Tucson, understood well that the current events of his time would become the history of the future. In the late 1800s, he became the treasurer of the Arizona Historical Society, founded by Arizona pioneers committed to documenting the history of the Arizona territory for future generations. His own letters, in the society archives, give insights into the events, culture, and values of the day.

Arizona in the mid-19th century, form the ceiling planks of the Tucson Presidio.

If you don’t know any stories about your ancestors, start where you are. Ask a parent, a grandparent, or an uncle about their life or a recollection of how a historical event impacted them. Record their stories, in writing or electronically, to preserve the details. Ask a lot of questions. And prepare to be amazed.

Like us, our ancestors did not live in a vacuum, and we cannot learn about them without learning about the times in which they lived. Their dreams and struggles, their triumphs and tragedies, and their character and attitudes were shaped in some way by the historical forces that affected their everyday lives.

If we are to make sense of their lives and of who we are, because of, or in spite of them, we need to embrace their historical and cultural context, just as our own descendants will need to do years from now to understand us.

History may be about the past, but it is our story, too, and it is up to us to know and preserve it for future generations.

************

Copyright © 2020 Linda Huesca Tully

I was never excited about history in school either. But I remember reading every biography I could get from the school library in the 4th grade. My Mom, who had thought I’d never read, didn’t know how to get my nose out of a book from then on.

I’m with you there, Cathy Meder-Dempsey. Biographies and autobiographies were the best! I still treasure reading the stories of Mark Train, Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and Thomas Jefferson. I always seemed to check out more books than I could carry from the library.

Charles and Pinkney are my 2nd and 3rd great grandfather’s too! Erin Tully

Love this! My love of history began when I was twelve, visiting Gettysburg and hearing from my grandmother that her grandfather fought in the Civil War (I found out later that it’s probably he was actually at Gettysburg). From colonial settlers to early 20th century immigrants, there’s so much history my family has experienced. It really makes it come to life when it impacts your family!

Thank you, Rebekah! I love that your family connection with Gettysburg brought the Civil War to life for you. Imagine the stories she must have heard. Oh, to be a fly on the wall!

Linda,

I am from Pinckney’s brother’s lineage. Edward Chaffin Tully was Pinckney’s brother who ended up marrying in Chihuahua Mexico and founded the Tully ranch in Bitterwater, San Benito County, California. I am sure you know that Pinckney passed away in Healdsburg, Ca and his grave stone is till there. Would love to meet up someday!

Darren, how nice to hear from you. I think Edward and Pinckney must have been close, as they seem to have gone to Chihuahua together, met their wives there, and both drove thousands of cattle into California before going into public service. You’re descended from quite the pioneer – famed lawyer, senator, and rancher! He lived a full life from his civic achievements to defending Tiburcio Vásquez. I’d love to know more about him. Isn’t he buried in Bitterwater? I haven’t seen Pinckney’s gravesite in Sonoma yet but hope to do so one day when we’re in the area.