|

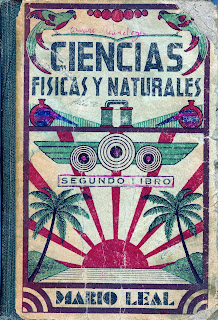

| My science book from the sixth grade at Ezequiel A. Chavez School, Mexico City, D.F., 1967 |

On my first day of school in Mexico City, I noticed something I had never seen back home in Chicago. As we entered the classroom, most, if not all, of the students kissed the teacher on the cheek as they greeted her with a “Buenos días, Maestra” – Good morning, Teacher.

Miss Ofelia Ortega Vázquez hugged each child back affectionately. Back home, as much as we loved our teachers, there was a certain distance between them and us. As I watched, I thought that the attractive lady in front of the blackboard might be quite nice.

At the end of the school day, the students thanked our Maestra, kissing her again on the cheek. After some time, I was doing it, too, not so much because my peers were, but because we seemed to enjoy a certain freedom to show our love for our teachers. Although the current climate of our society today might not allow for this display of affection, at that time it was considered genuine and innocent, as far as I know.

Showing me to my seat, the Maestra explained in English that she was about give us a spelling quiz. I remember it well. Miss Ofelia paced up and down the rows of desks, repeating each word three times. I tried my best to listen carefully to the words and write them down phonetically, but I failed miserably.

Señorita Ofelia Ortega, or Maestra (teacher), as she was called, was in fact not a Miss, but a Mrs. who had been widowed at a young age. She was in her mid to late 30s, tall and slender, with a freckled face framed by short, soft brown curls. Her benevolent dark eyes danced when she laughed, and her voice, confident and reassuring, could command the room with a single word. She moved purposefully through her classroom, not missing a beat, pointing out mistakes and exacting nothing less than perfection from her students while spending extra time with those who needed it most.

Recess was a repeat of our morning arrival at the school, as scores of well-meaning but curious girls again surrounded my sisters and me, poking their fingers through our ringlets and peppering us with questions. Some of our new schoolmates knew enough English to ask us our names and tell us theirs. In giggly voices and heavy American accents, we repeated their names in singsong fashion, much to their amusement. Mrs. Rangel, the principal came to our rescue as she had that morning, but this time we were beginning to enjoy the attention, so she left us alone. By the end of the day, the three of us had made new friends.

Early that afternoon and many times after that, my mother picked my sisters up and let me go home with Miss Ofelia. As soon as we got there, she’d pull on a checked print apron embroidered with red roses along the neckline and on the large pockets at the hem. She would sit down with me at the kitchen table and go over the day’s lessons, leaving me to do my homework as she started dinner.

She paid close attention to my work, looking over my shoulder now and then, helping me conjugate a verb or explaining when to add an accent mark. She wanted me to study hard so I could speak, read, and write Spanish as well as any native speaker. Still, she made sure there was always time for play, and when it was time to go home, she sent me off with a big hug.

Miss Ofelia would teach my class through the sixth grade, our last year at Ezequiel A. Chavez School. Whether or not it was standard practice, it made sense in that she knew our backgrounds, strengths, and weaknesses well. We too, got to know our Maestra well and not only respected her but loved her, too. Our class was cohesive and well-behaved and studious for the most part. Though there may have been exceptions, we were as loyal to our teacher as she was to us.

My parents and Miss Ofelia hit it off, and she was a guest at our home several times. Even after we left Mexico City, our family stayed in touch with her for many years. When I was in the ninth grade and ready to make my Confirmation in California, I wrote to ask her to be my godmother. It would be a symbolic gesture as she could not afford to fly up for the Mass, but still I was thrilled when she accepted. Now I would get to call her not just Maestra but also Madrina, which means godmother. It would mean an even stronger bond between us.

Miss Ofelia made a place for me in her class and in her heart. She will always have a special place in mine.

Copyright © 2013 Linda Huesca Tully

She sounds really inspirational – interesting to hear the very different approach in Mexico.

I have started a new blog hop – The History Hop – that allows history bloggers to link up their favourite posts every week

Blog hops provide an opportunity to share posts and to meet other bloggers and I'm hoping that the History Hop will prove

a great way to reach a wider audience and to meet other history bloggers of all sorts.

I would love to see your posts linked up,

Alice @ We Came From

Thank you for you kind comment, Alice. The History Hop sounds interesting, too. I'll have to check it out!