José Enrique Florentino Huesca (1847 – 1919)

María Angela Catalina (Perrotin) Huesca (1893 – 1999)

Gilberto Huesca (1912 – 1915)

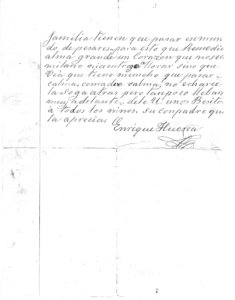

Condolences

Tierra Blanca

My Dear Friend,

As I send you my greetings together with all the well-deserved attentions to you and your kind family, I want to send you my deepest sympathies on the death of the Child Gilberto, and you must not believe that it was caused by a Cold, but by the bump he had on his head, which sooner or later would have a sad ending. It happened…there is nothing you can do but have patience.

Now do not give in to the Pain; but Look at this news with some calm, understanding that it is better to grieve over the dead rather than wish them alive again; as I did, for I have spent my life in tears wishing they were alive.

The conjugal bond offers us flowers and pleasures…but the cross of marriage, offers us a world of woes. No matter how much a family may possess, all must go through that world of woes…but all you can do is have a big soul, a Heart that neither denies the truth nor gives in to tears but Sees that this is part of life.

Calm, my friend, calm, do not give in and do not carry this burden around with you. Give my kisses to all the children.

Your friend who esteems you,

Enrique Huesca

Florentino Huesca, of Cañada Morelos, Puebla, Mexico, wrote to his daughter-in-law, my grandmother, Angela Catalina (nee Perrotin) Huesca, in Tierra Blanca, Veracruz, Mexico, shortly after the death of her young son, Gilberto Huesca.

Gilberto was about two years old when he died. The exact cause of death is unclear; many of the civil records of the village of Tierra Blanca from 1915 were burned in a fire, and most of those who might have known the details have gone on to their heavenly reward.

The letter mentions little Gilberto had a bump on his head. Did he fall or suffer a blow to the head while playing or pulling down some heavy object from above? Could it have been a tumor of some sort? We may never know, but we can certainly imagine the grief young Catalina felt at losing her sweet little boy.

She may have been feeling some guilt, too, as she seems to have believed her son had died of a cold. Enrique gently reminds her of the bump and adds that “sooner or later,” it would have ended sadly. In what must have been nearly unbearable for Catalina to conceive, he tries to reassure her that the child’s fate might have been worse had he lived.

His words today might sound terribly fatalistic, but they came during a trying period in Mexico. The country was in the throes of a revolution, and Tierra Blanca and surrounding areas not only experienced the heavy casualties of that conflict but also lost many people, young and old, to outbreaks of measles, diptheria, and smallpox.

It would have been easy for a young 21-year-old mother to “give in to the pain” of losing her child when she was scarcely an adult herself. But her father-in-law’s words must have given her the strength she needed to go on and care for her husband Cayetano and their three children, Enrique, Eduardo, and Victoria, even as she was in the first trimester of yet another pregnancy.

Like many of the women of her time, Catalina would prove to be strong and resilient. She and Cayetano would have 17 children in all, 11 of whom survived into adulthood.

+Huesca,+Eduardo+Huesca,+Cayetano+Huesca,+and+Enrique+Huesca,+Orizaba+ca+1912-1913.jpg) |

| Catalina and Cayetano Huesca and sons (left to right) Gilberto, Eduardo, and Enrique, in front of their home, Orizaba, 1913. |

Enrique’s letter hints at his own trials and tribulations. We know little about him except that he was born between 1847 and 1850 in Puebla, Mexico, to Jose Calletano de la Trinidad Huesca and Josefa Rodriguez. A devout Catholic, he followed in the family trade as a carpenter, crafting interior furnishings for the cathedral and churches of Puebla, a city known for having as many churches as there are days in a year. He taught his children to do good for others but to keep their acts to themselves, often reminding them to “never let the right hand know what the left hand is doing.” This was a refrain that his children and their children would carry with them all their lives.

Born at the end of Mexico’s civil reform war, Enrique lived through some of the most turbulent eras of his country’s history. Before he had even reached his teen years, he undoubtedly witnessed the Battle of Puebla between the French and Mexican armies. He would have rejoiced wildly with his family at the Mexican victory on May 5, 1862, only to be devastated barely a year later when the French regrouped and defeated the Mexicans in a second battle at Puebla and went on to topple and replace the Mexican government with what Napoleon III referred to as his “Mexican Empire.” He and his parents would have discussed the resurgence of the deposed Mexican president, Benito Juarez, who, with the backing of President Abraham Lincoln, reclaimed his government and had the puppet Emperor Maximilian Hapsburg executed by firing squad in 1867.

The uncertainty of the times and their severe impact on the nation would continue for many years as subsequent regimes rose and fell one after the other, culminating in the Revolution of 1910 and indelibly scarring the psyche of the Mexican people with the ironic realization that the only constancy in their lives was that – save their faith in God and their love for one another – nothing, including happiness, could either be certain or last forever.

Next: Sentimental Sunday – “Do Not Give In” Part Two

Copyright © 2012 Linda Huesca Tully